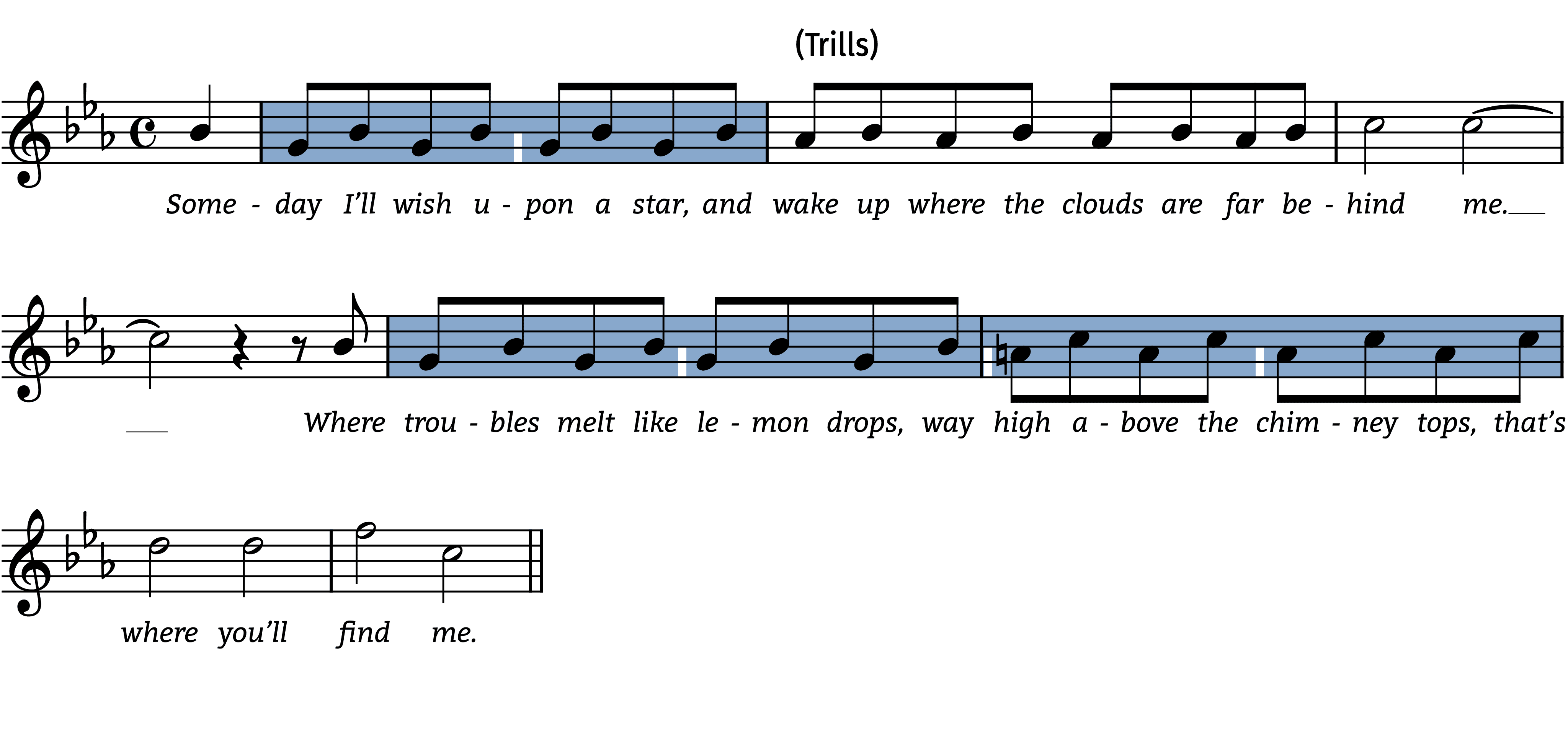

Actually, we have—just not for a long time.

Musicians in the late Renaissance and Baroque eras revered melodic prowess, considering it the hallmark of a master musician. This admiration fueled an obsession among aspiring musicians, pushing them to pursue rigorous training wherever they could find it. At the time, this meant mastering skills like partimento, solfeggio, and counterpoint. Such methods started with a basic harmonic template—a “schema”—and challenged students to elaborate it using basic melodic patterns known as “diminutions,” or what we might now call melodic figures.

For some modern comparisons, we have the 12-bar blues, ii-V formulas, or the i-VII-VI-V progression—all standard fare in jazz and rock. And jazz and rock students tirelessly practice riffs (“diminuti”) in every key so they’re ready to assemble them freely over these standard schemas whenever inspiration strikes.

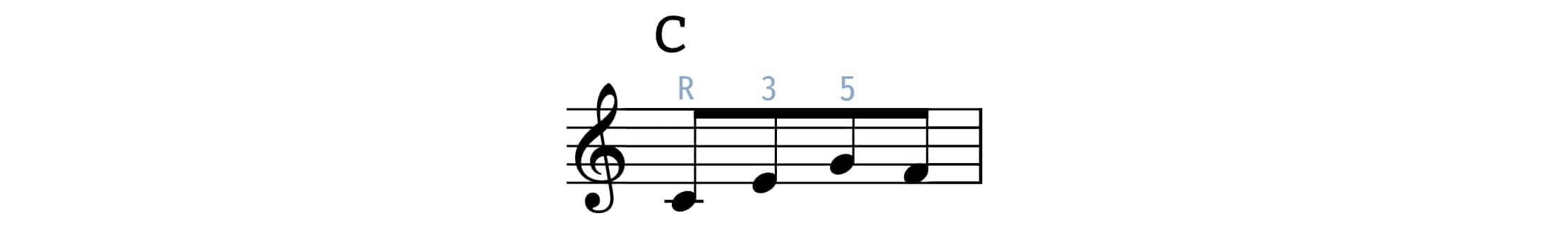

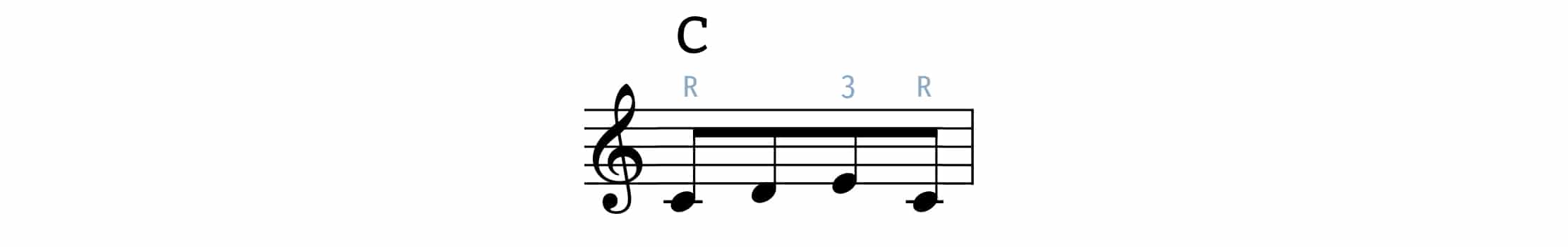

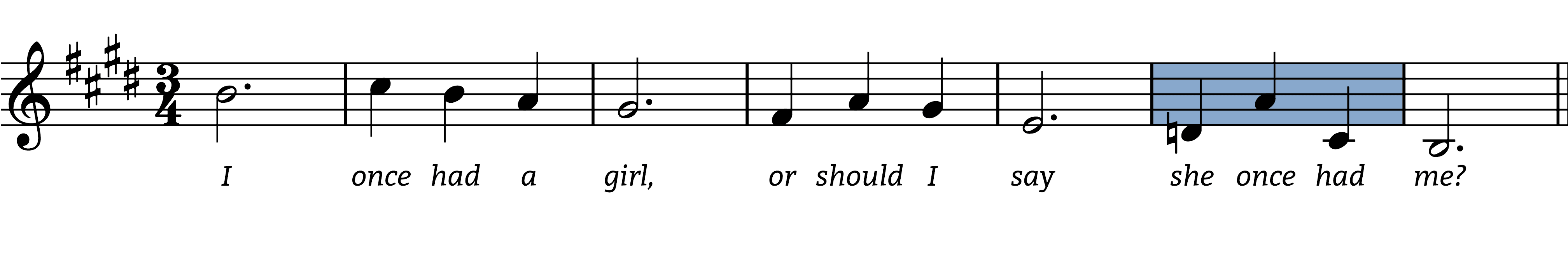

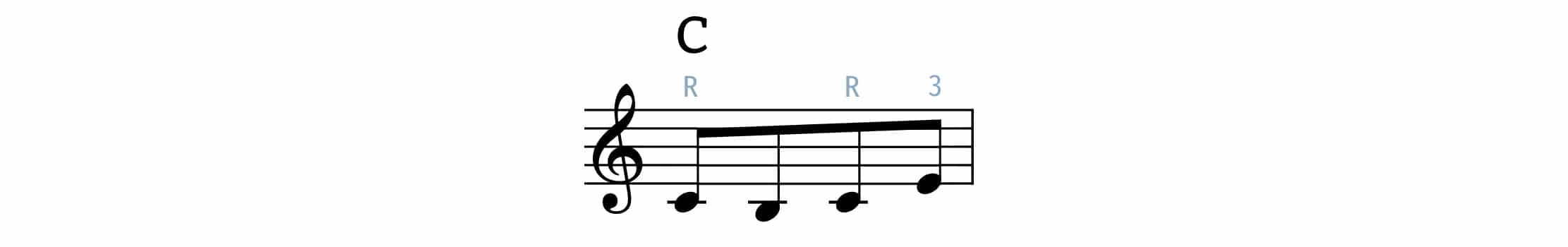

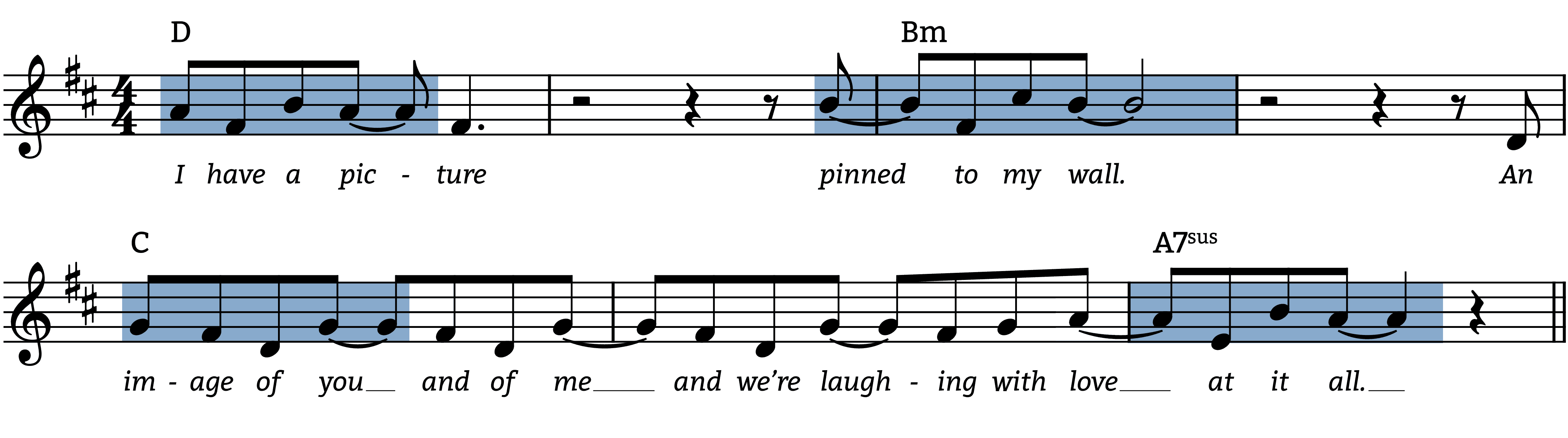

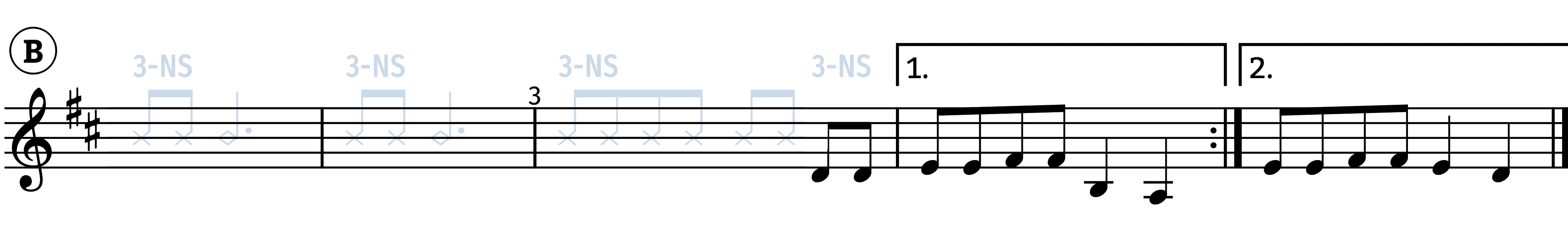

Take the i-VII-VI-V progression, for example.

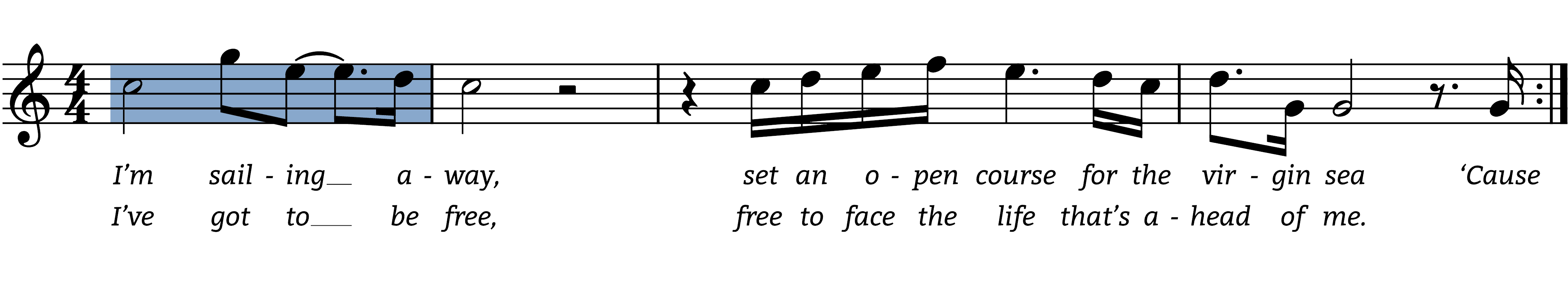

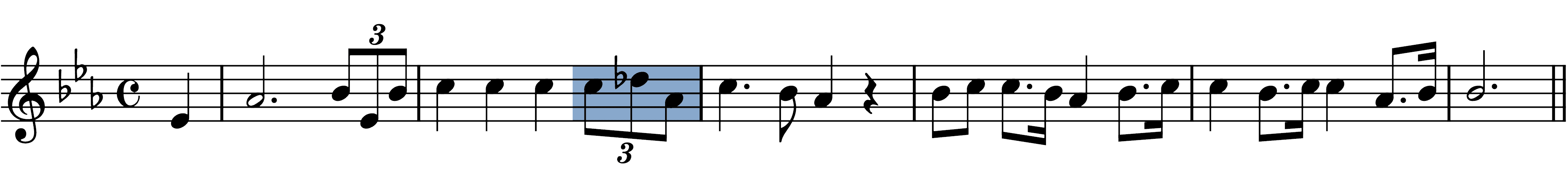

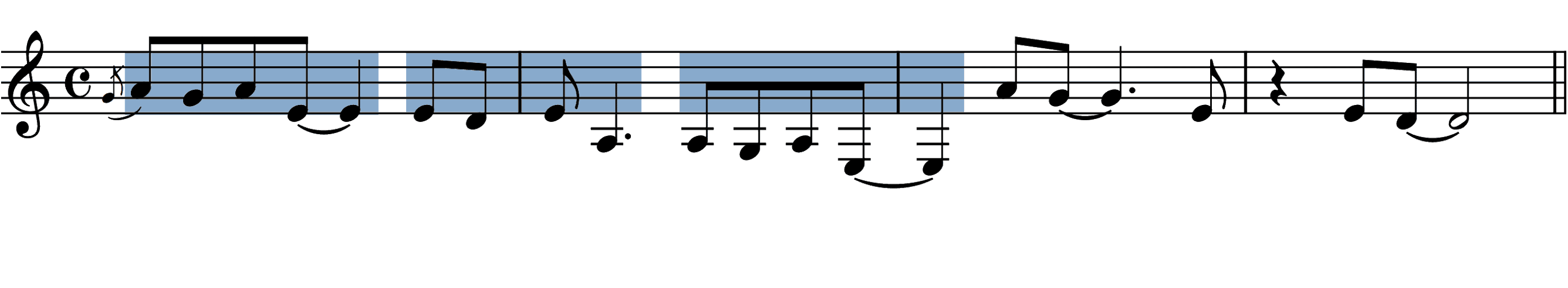

This iconic rock solo shows a natural integration of melodic riffs over a simple schema.

Guitar solo from “Stairway to Heaven,” by Jimmy Page and Roger Plant

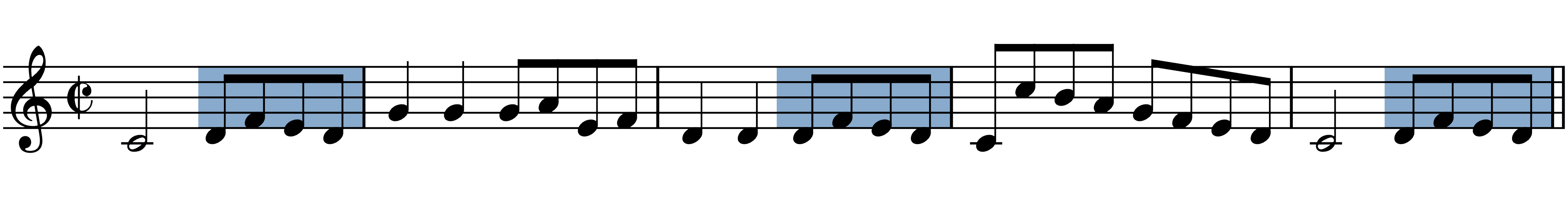

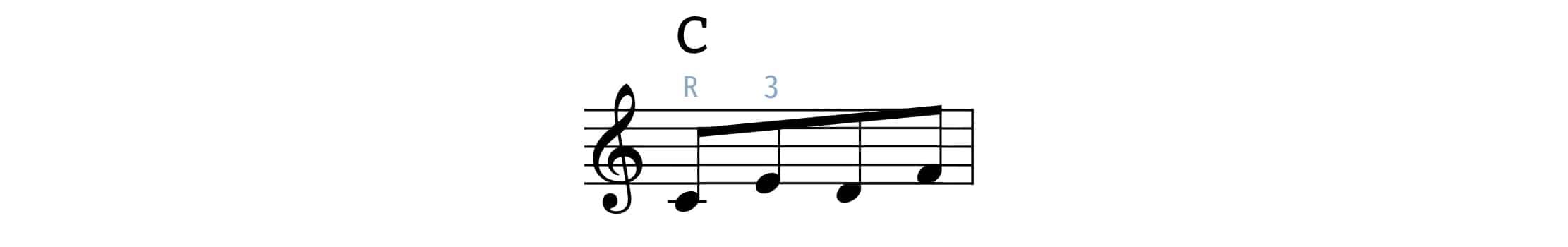

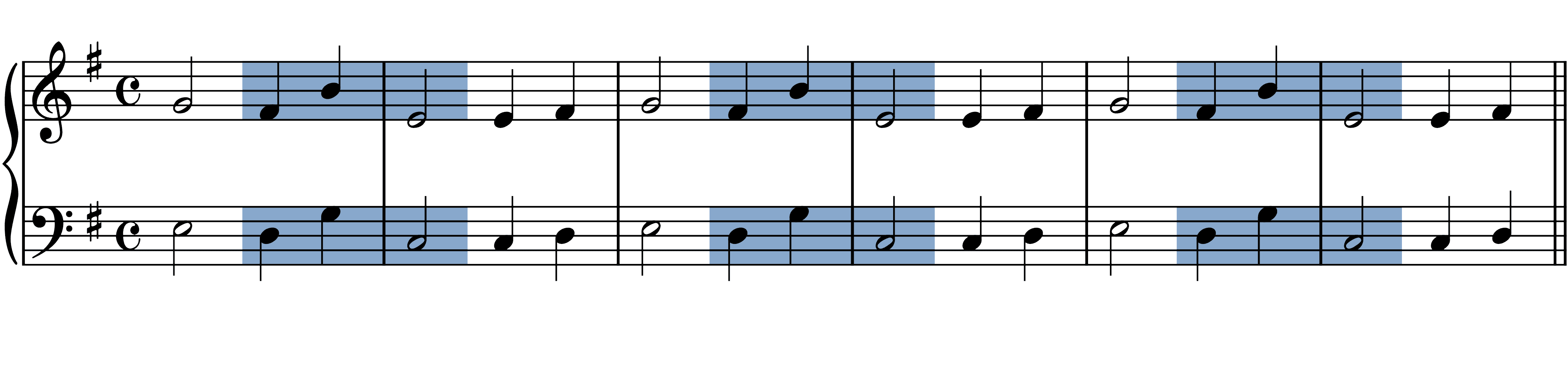

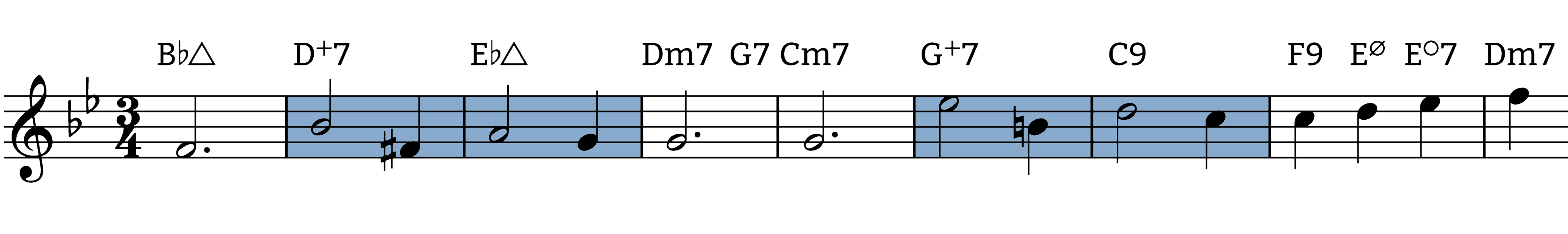

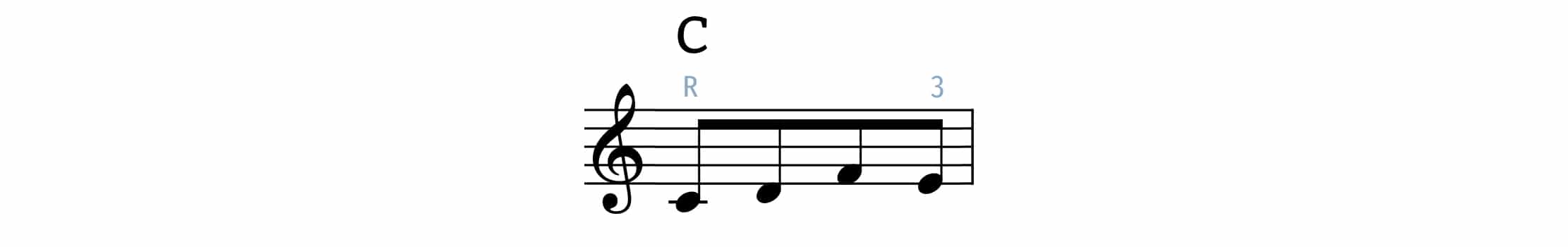

Back to the late Renaissance. Before tackling improvisation with diminuti, students first mastered “the Rule of the Octave,” an exercise that challenged them to play harmonies in elegant, clever ways over ascending and descending scales. Here’s but one solution.

“Francois Campion’s ‘Rule of the Octave’” (1730)

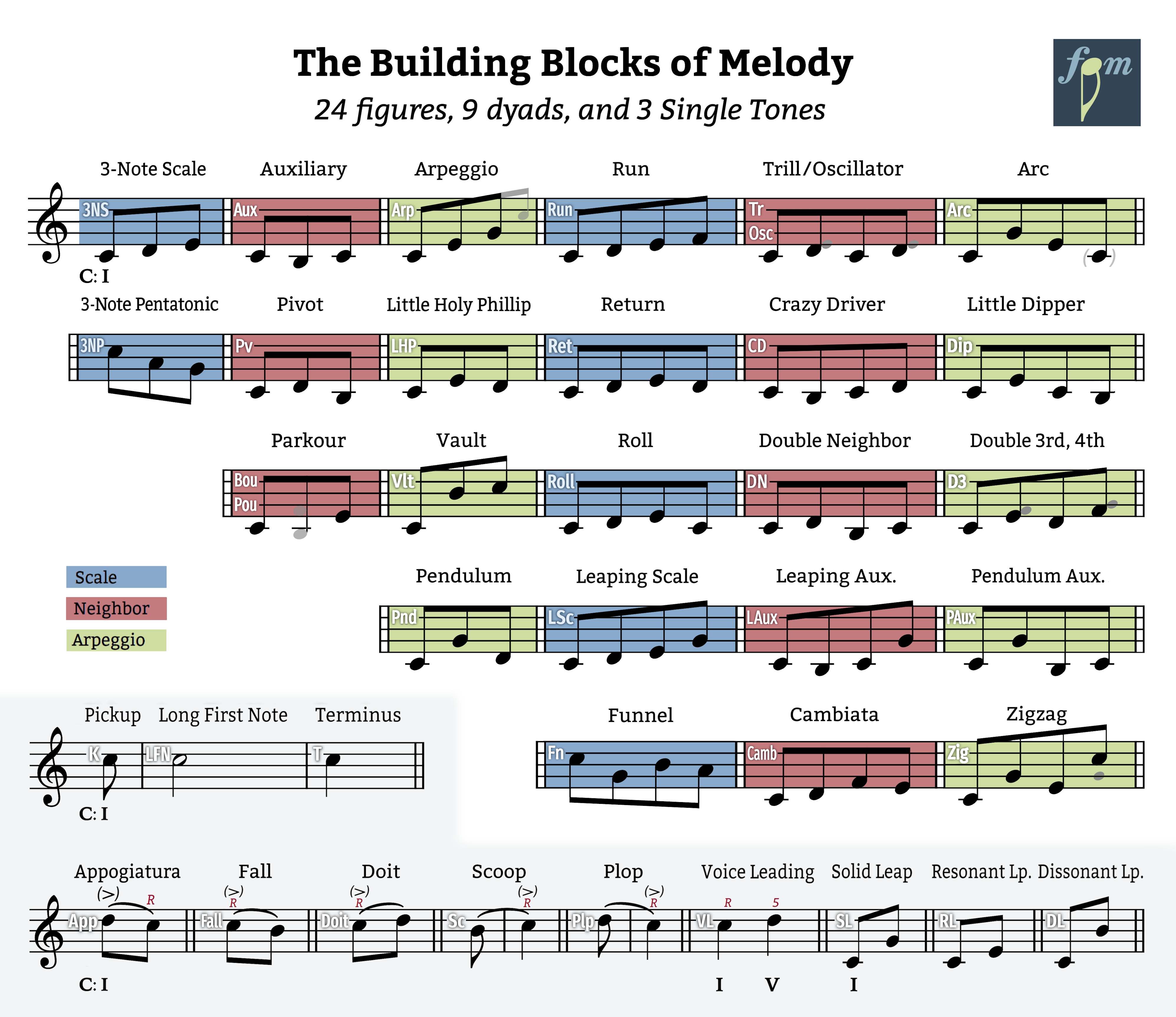

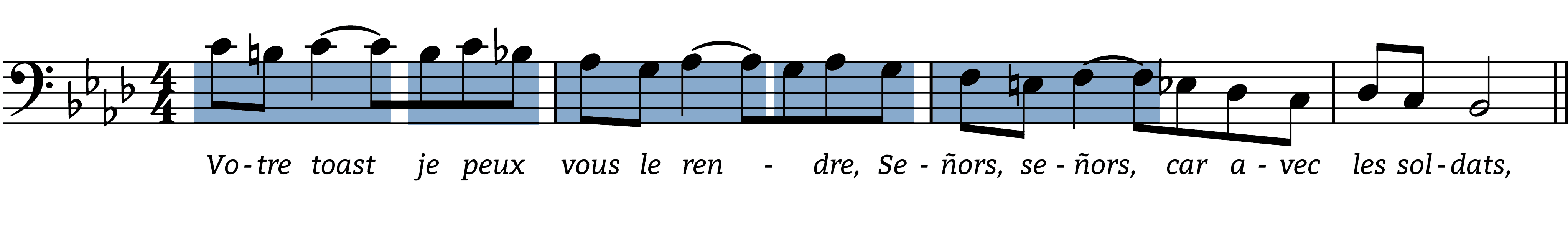

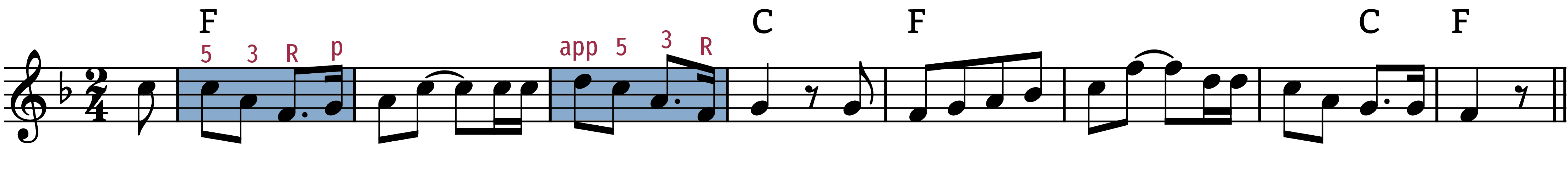

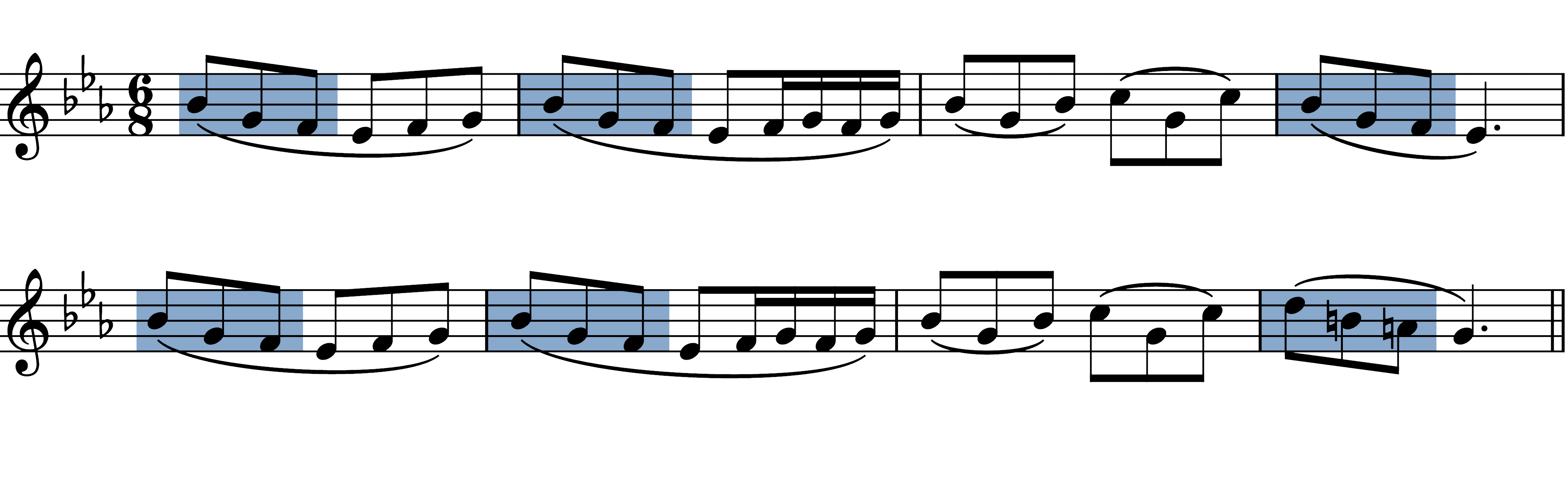

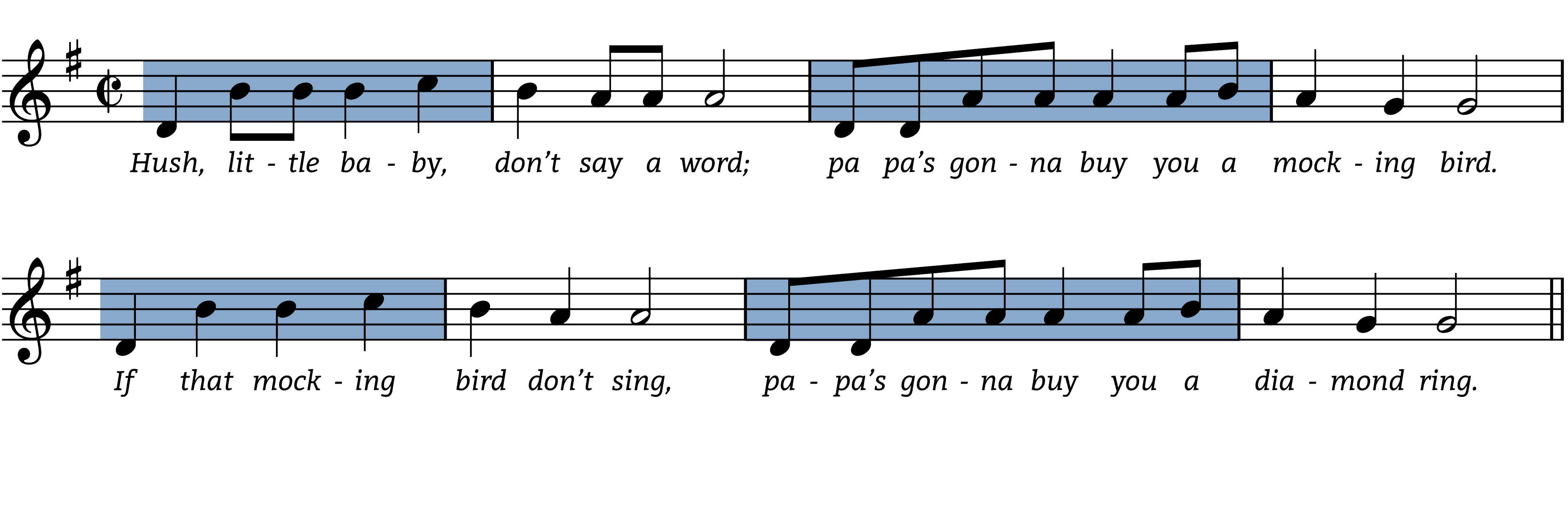

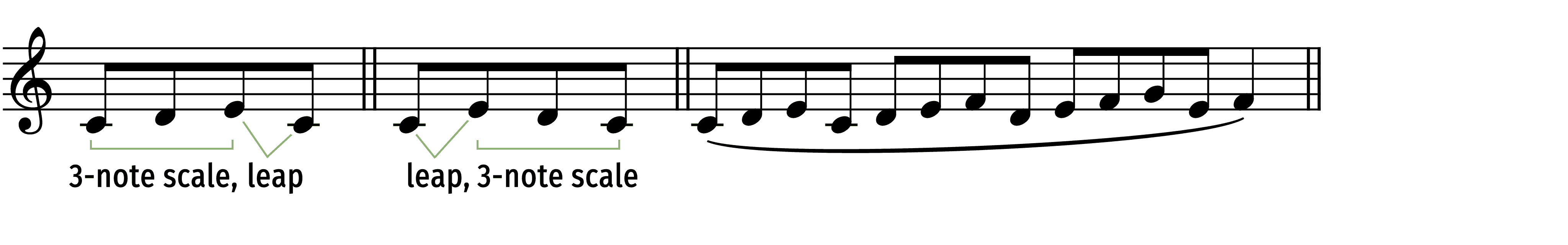

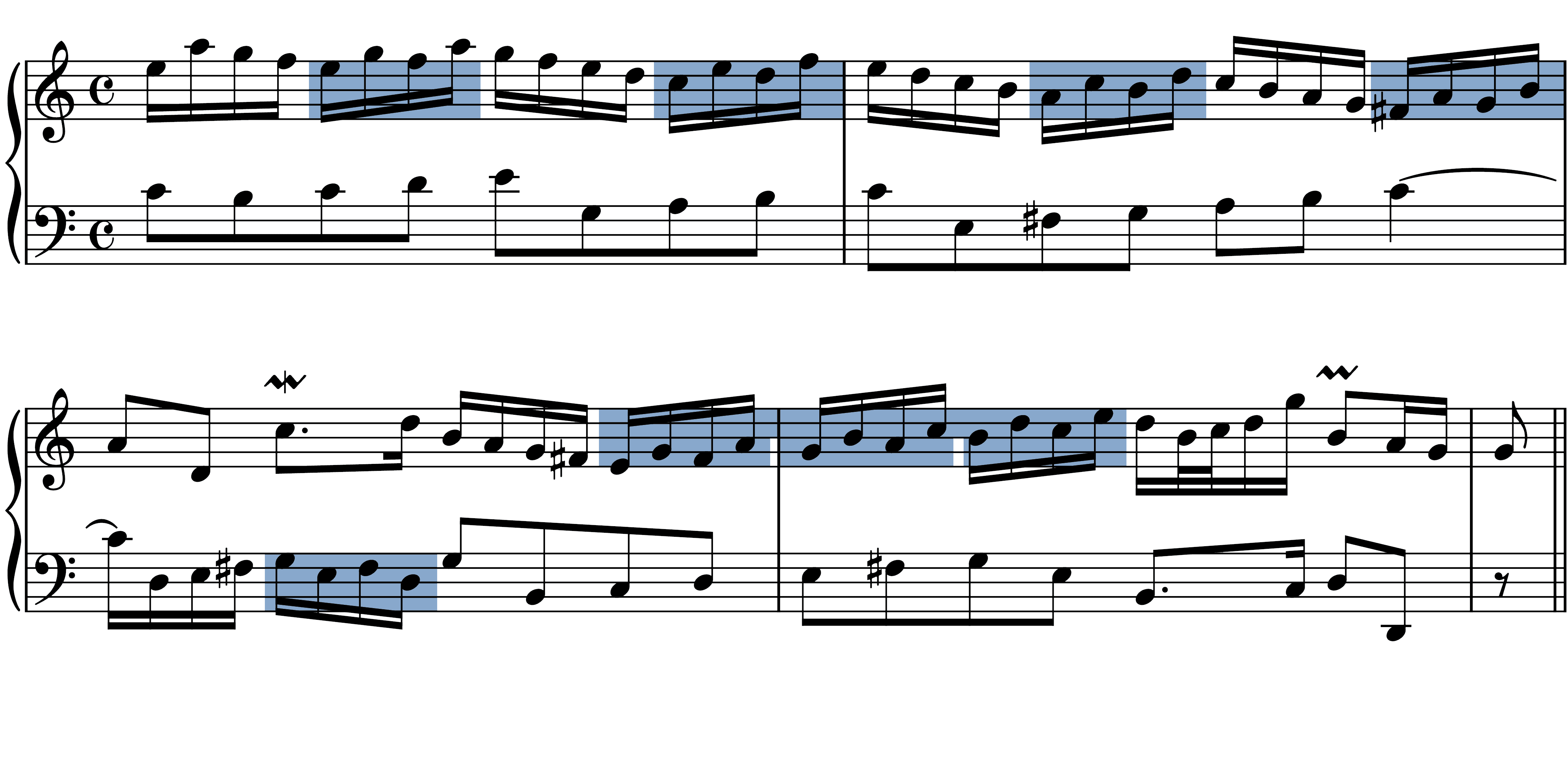

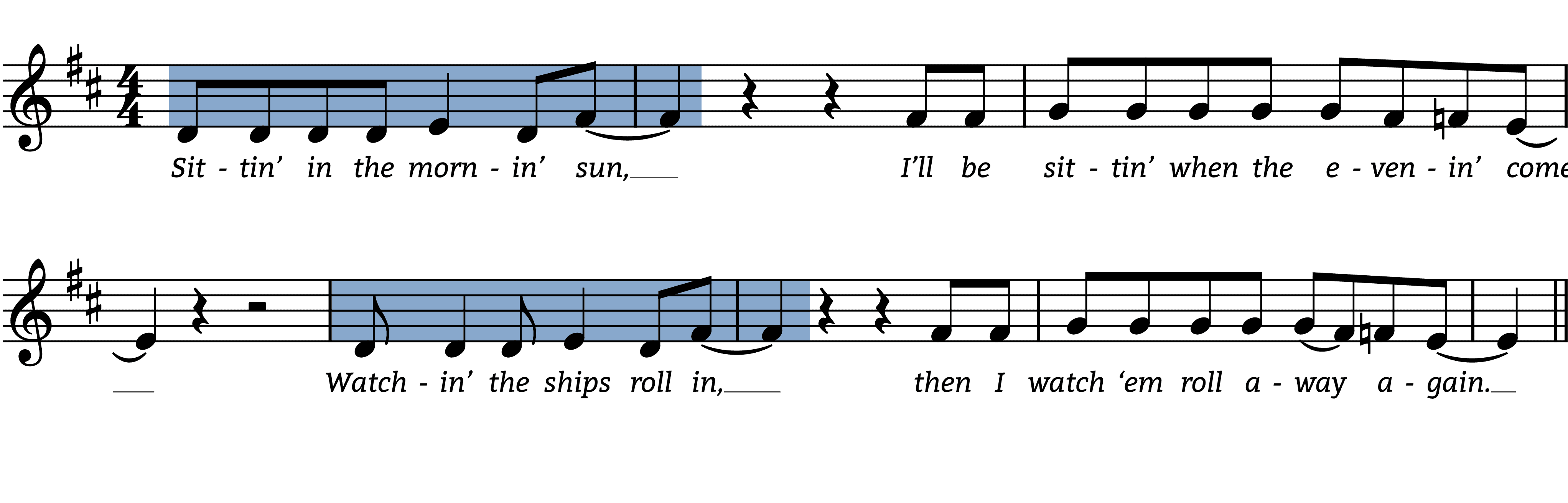

As students advanced, they worked through exercises like those found in Francesco Durante’s Partimenti Diminuti. This collection includes 103 basslines for students to improvise over using specific diminuti. Here’s “Partimento #9” as it appears in that volume. I’ve labeled its diminuti with figure names from my BBM table. (And—a quick scan of this bassline makes it clear why students learned the rule of the octave!)

“Partimento #9,” from Partimenti Diminuti by Francesco Durante

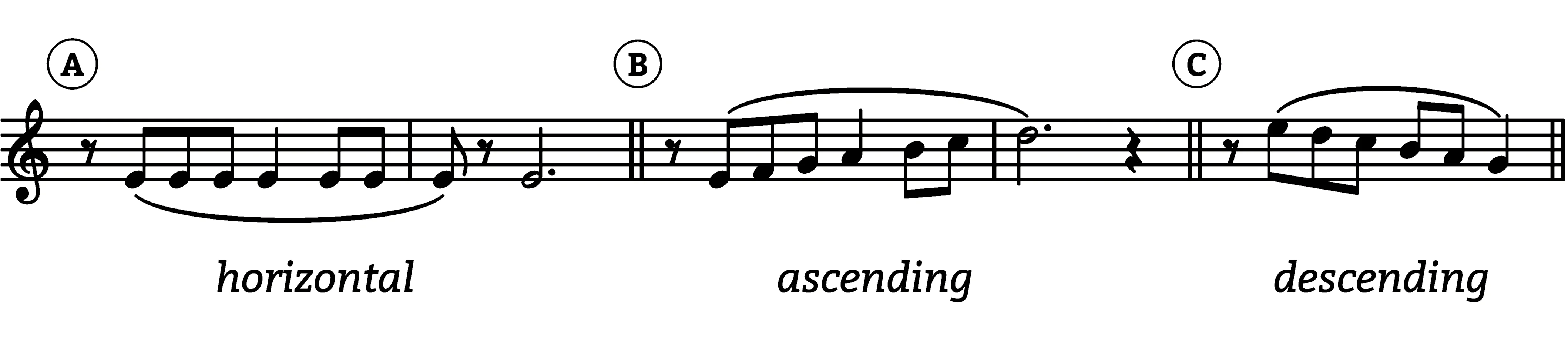

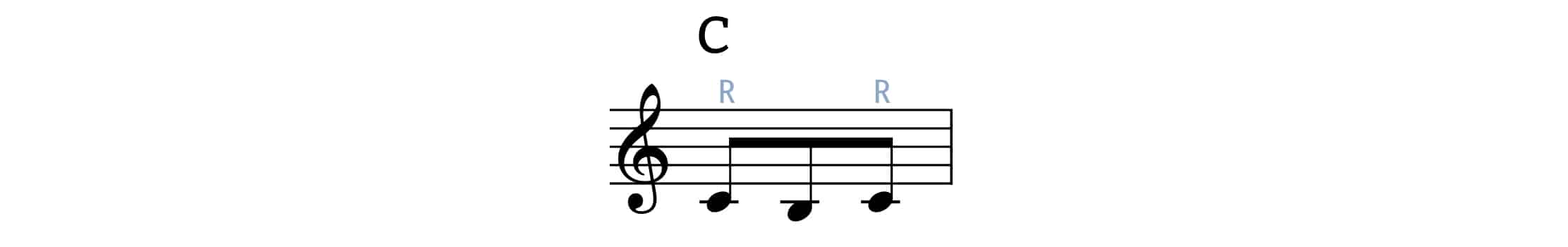

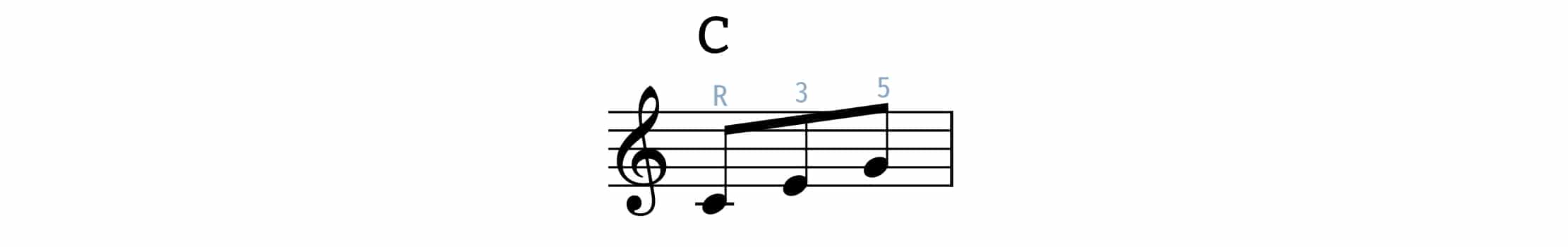

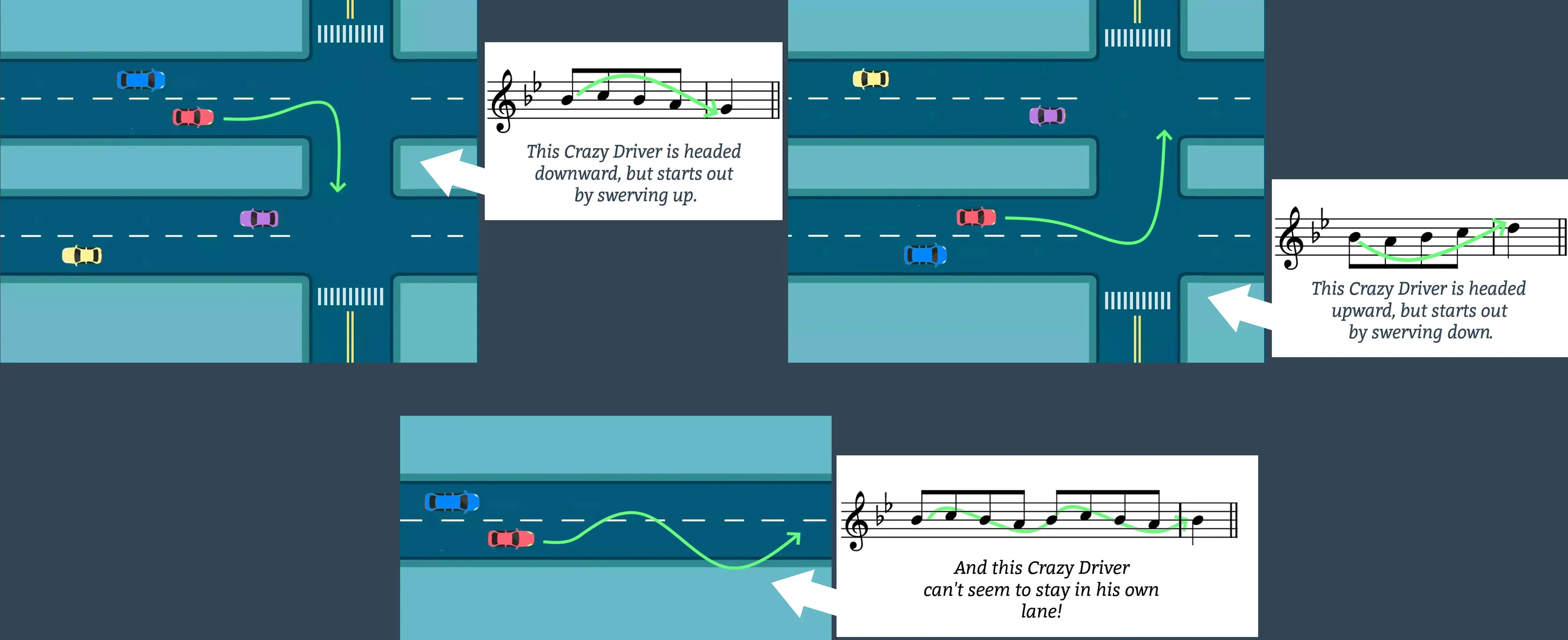

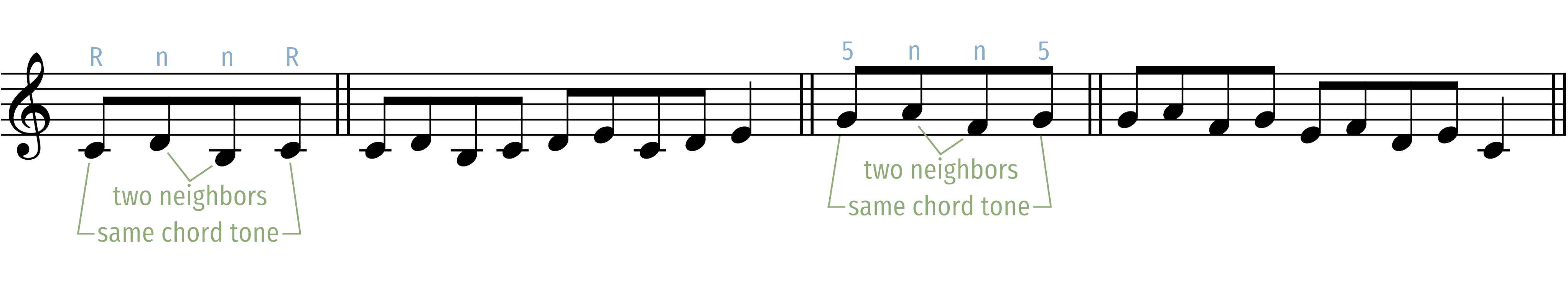

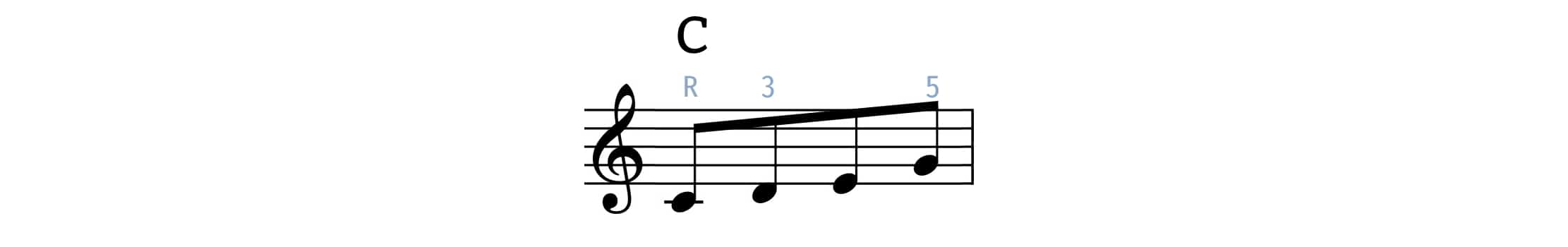

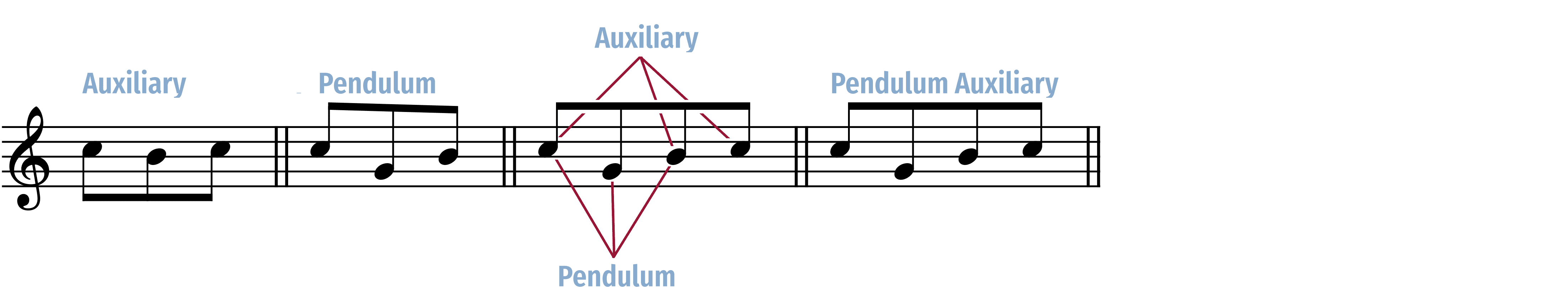

A few teachers even named their diminuti to help students internalize them. Take this excerpt from Michael Wiedeberg’s The Self-Taught Keyboard Player (1775), for example.

Why did partimento fade away?

Partimento, which emerged during the Enlightenment, drew heavily from earlier pedagogical approaches centered on training improvisation with melodic figures. As a result, it did not reflect the Enlightenment’s emphasis on concision, logic, and systematic thought. Gradually, these ideals began to reshape musicians’ understanding of music, redirecting focus from melodic figures to harmonic progression and voice leading.

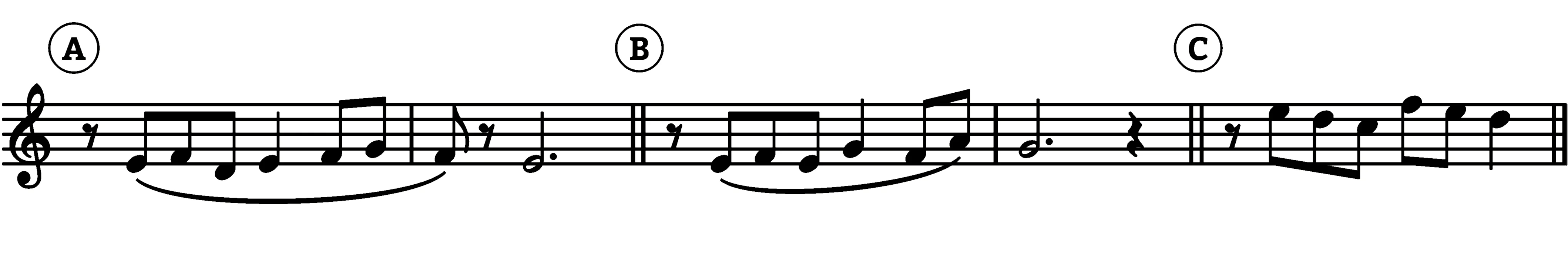

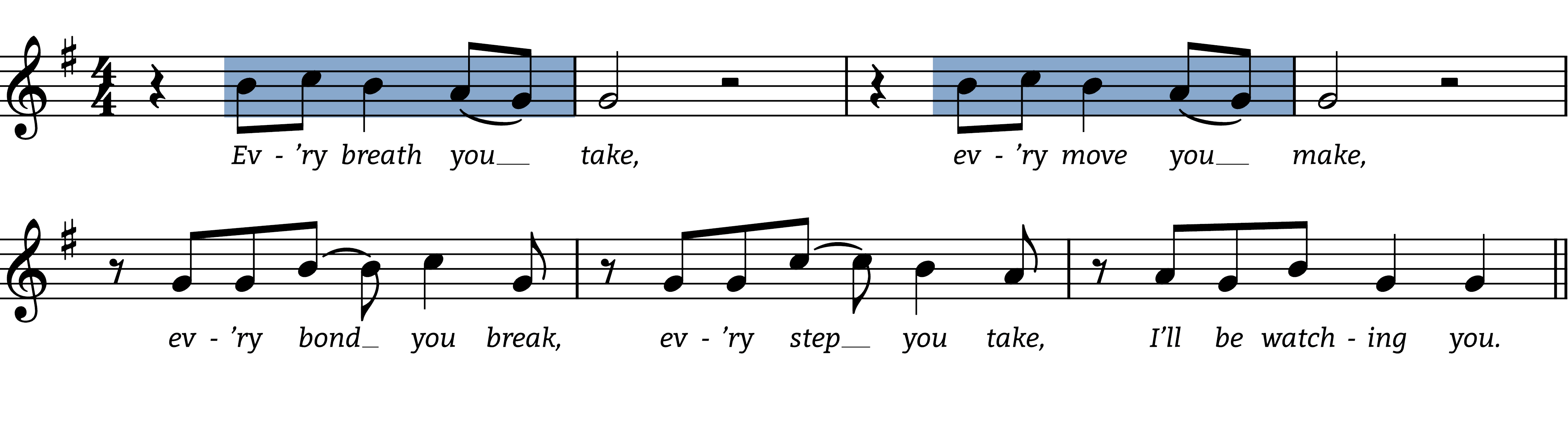

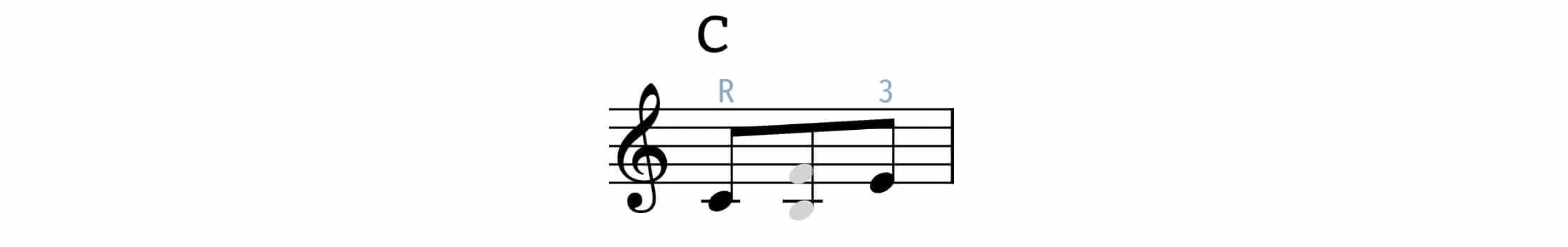

Composers like Rameau, Reicha, and Weber laid the groundwork for functional tonality, emphasizing harmonic principles over melodic spontaneity. Johann Philipp Kirnberger, a student of J.S. Bach, formalized these ideas in his teaching method, which centered on chorale harmonization. Students embellished the soprano line with passing tones, neighbor tones, and chordal leaps. This “embellishment approach” still dominates how melody is taught today, even when the four-voice chorale is replaced by choosing chord tones from a harmonic progression.

Two screenshots from Gareth Green’s YouTube video series “Music Matters.”

Adding embellishing tones to a framework of chord tones and calling it composing is like adding ketchup and mustard to a hot dog and calling it cooking. Even when a diligent student follows this approach perfectly, the best they can hope for is a “classroom melody”: something stiff, trite, and unmusical. Early AI-generated melodies suffered the same fate as they relied on these same legalistic techniques.

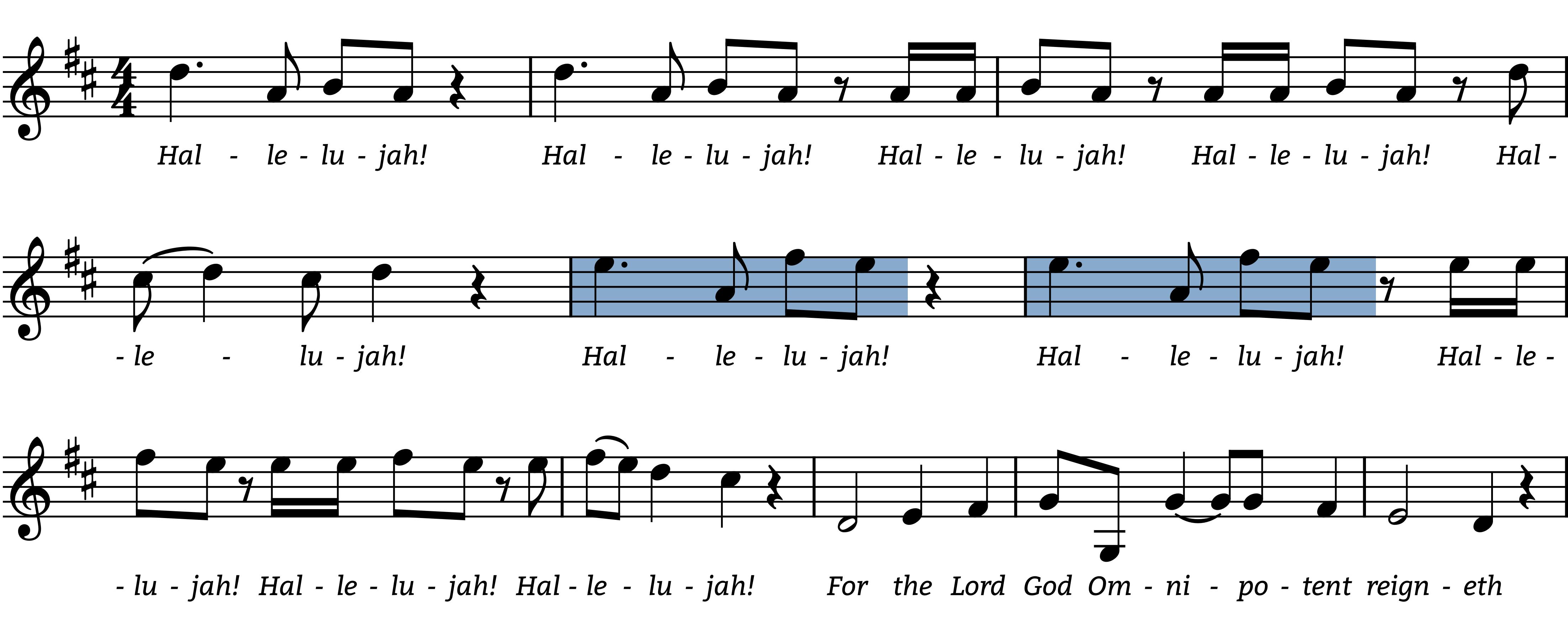

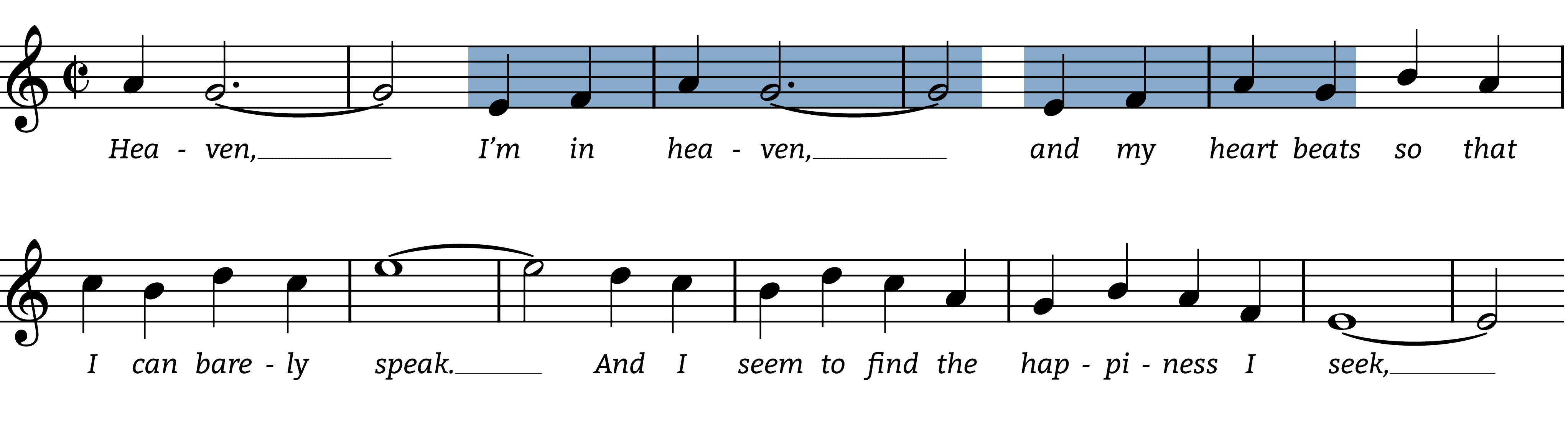

SCHEMAS AND DIMINUTI IN MODERN MUSIC

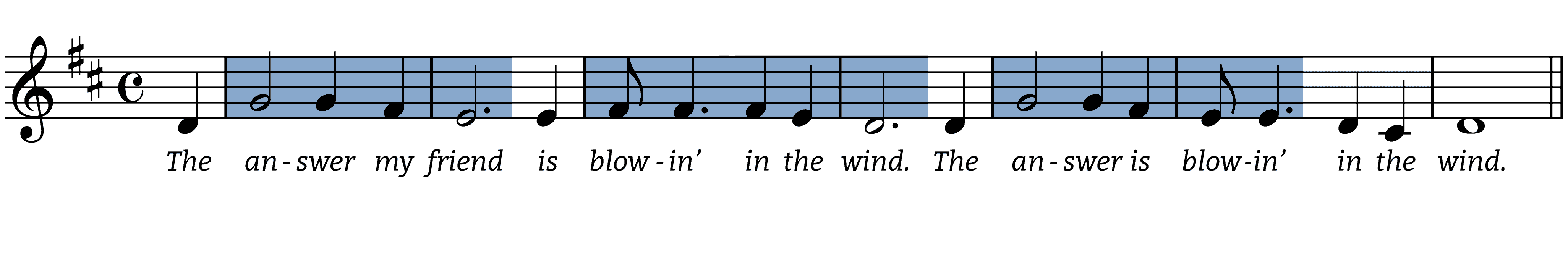

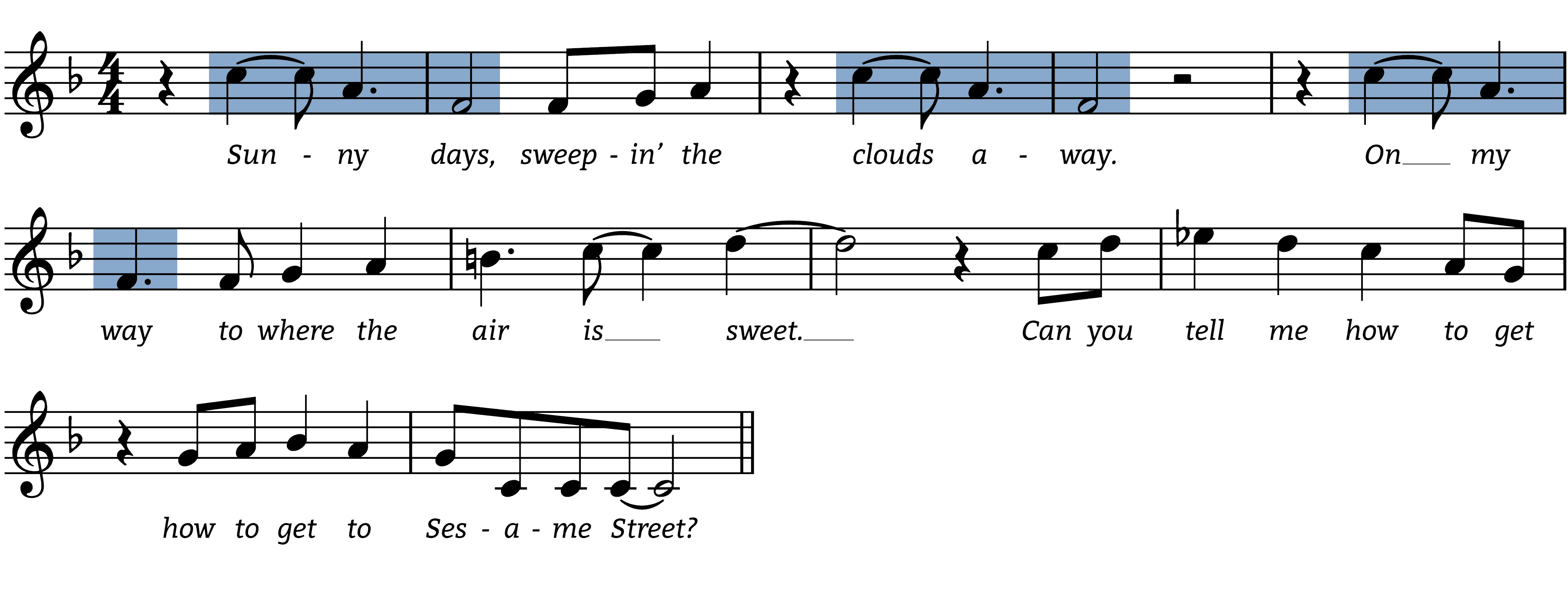

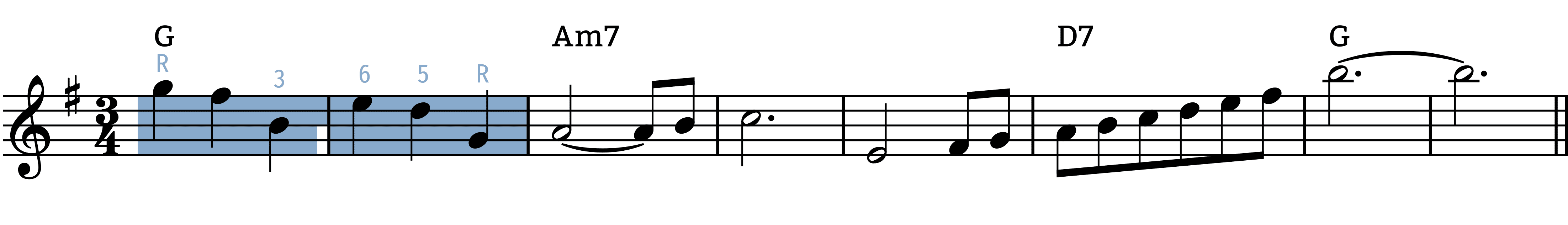

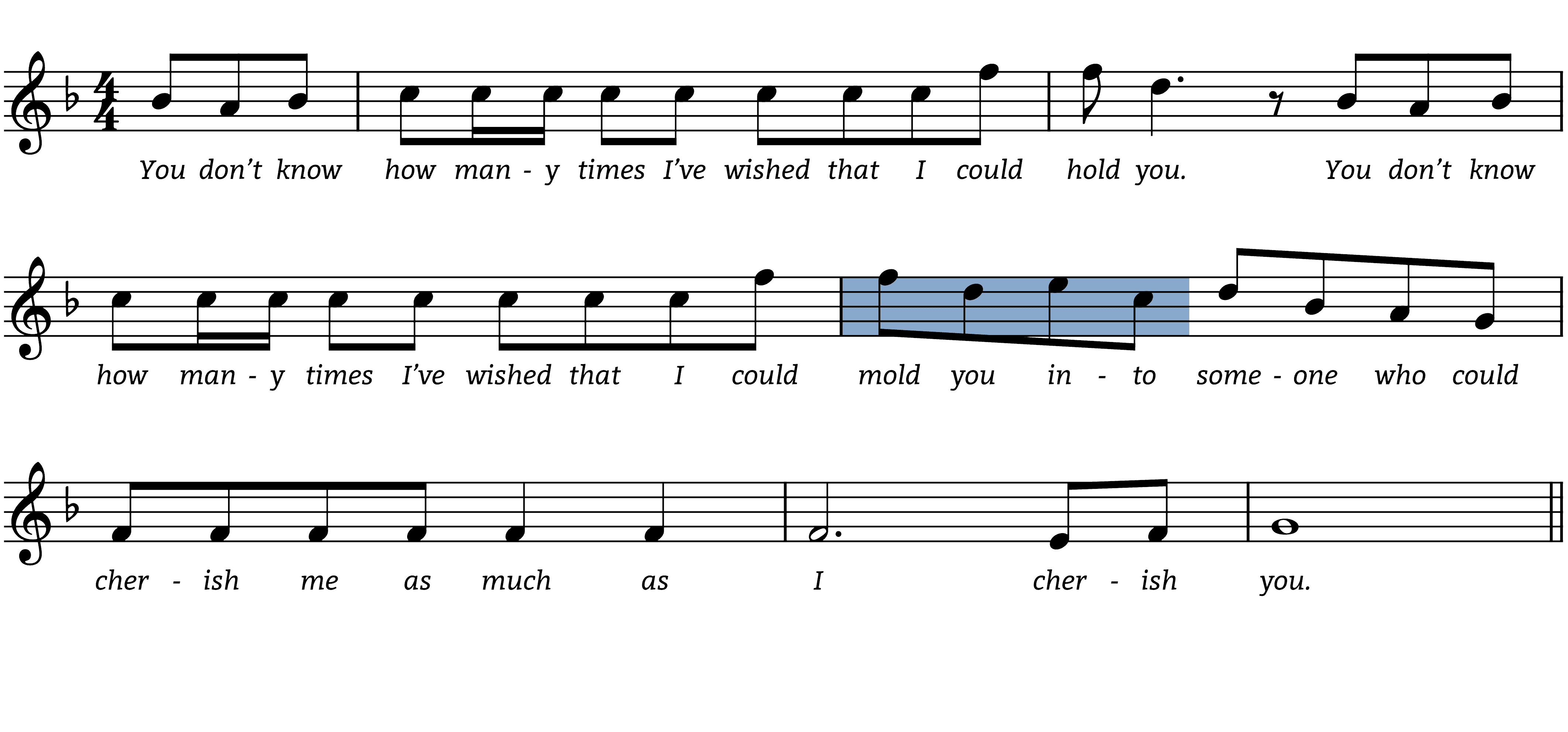

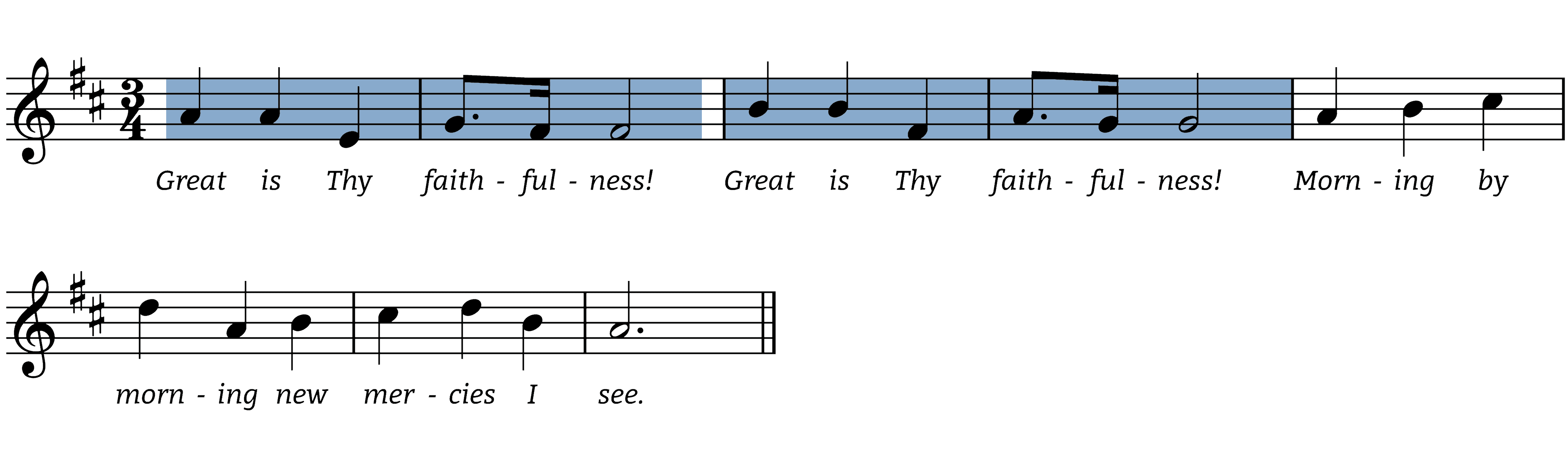

Schemas and diminuti may seem to have gone the way of typewriters, road atlases, and landlines, but actually, they’ve remained active in the musical imagination. In fact, they appear in every tonal style. I’ve already mentioned a few progression/schemas in jazz and rock. Here’s the most famous progression in pop music: I-V-VI-IV—that’s right, another schema! This progression has spawned hundreds, if not thousands, of songs. But what nobody talks about is how so many melodies can be built over the same four chords. The answer: melodic figures (i.e., diminuti).

The “Axis of Awesome Progression,” a.k.a. the “Pop Progression”

SO, HOW DO MUSICIANS LEARN MELODIC FIGURES?

The same way we learn our native tongue: through exposure over time. In the case of melodic figures, we acquire our native musical language through three types of exposure—the ears, the fingers, and the eyes.

1. Exposure through listening.

The musical ear is incredibly skilled at recognizing and following patterns. We naturally group musical elements into meaningful “chunks” based on innate organizational principles. Melodic figures align with the underlying meter, making it easier for the brain to process and learn patterns, much like we learn language.

2. Exposure through playing.

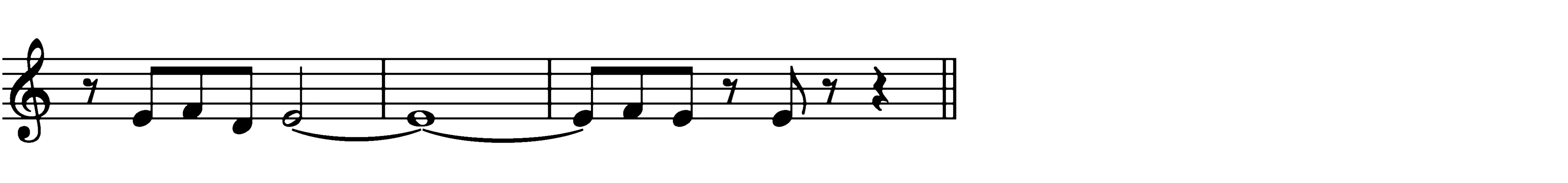

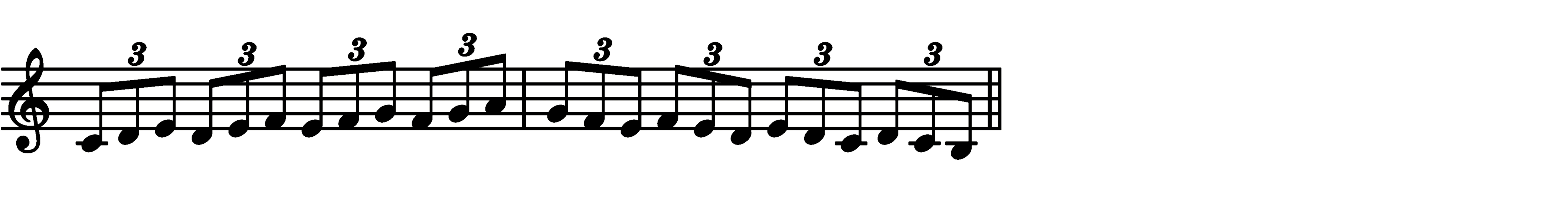

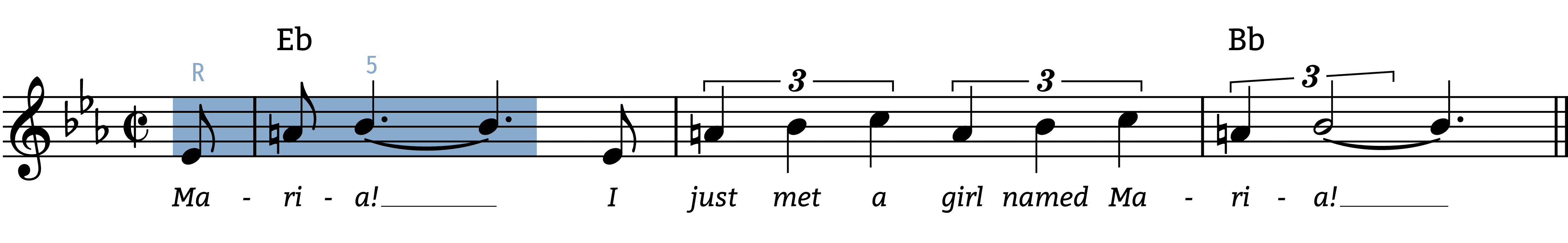

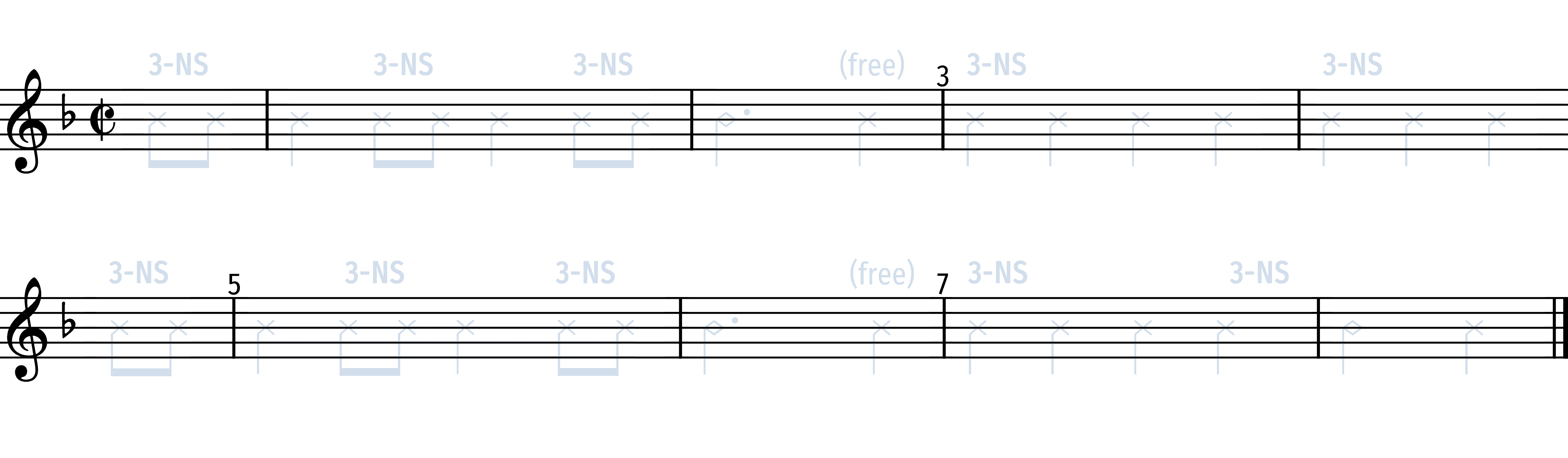

Most musicians have basic melodic patterns embedded in muscle memory through finger exercises. For instance, Hanon’s piano exercises include nearly half of the figures on my Basic “Building Blocks of Melody” table (below) in their first ten examples.

“The Virtuoso Pianist,” by Charles-Louis Hanon

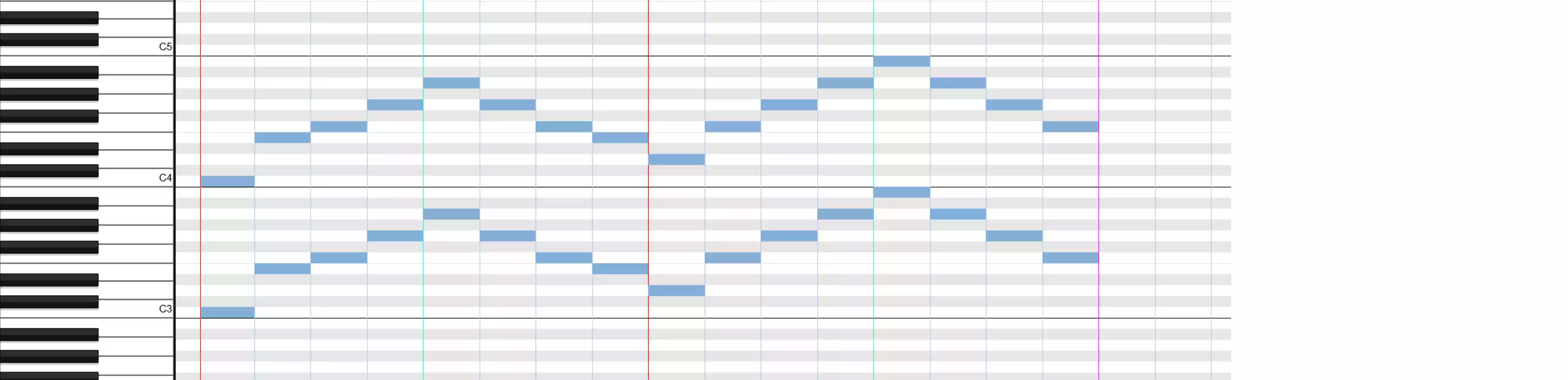

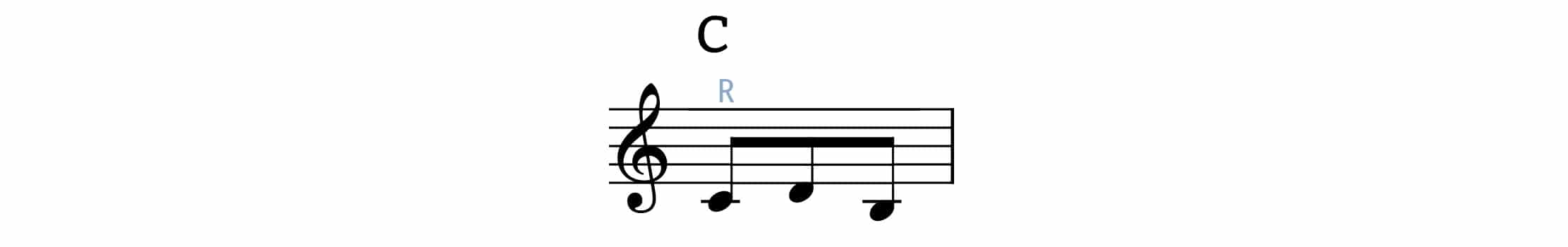

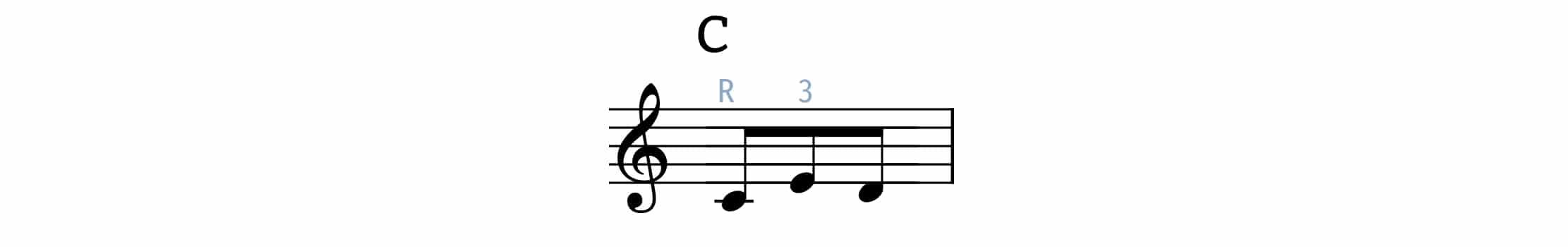

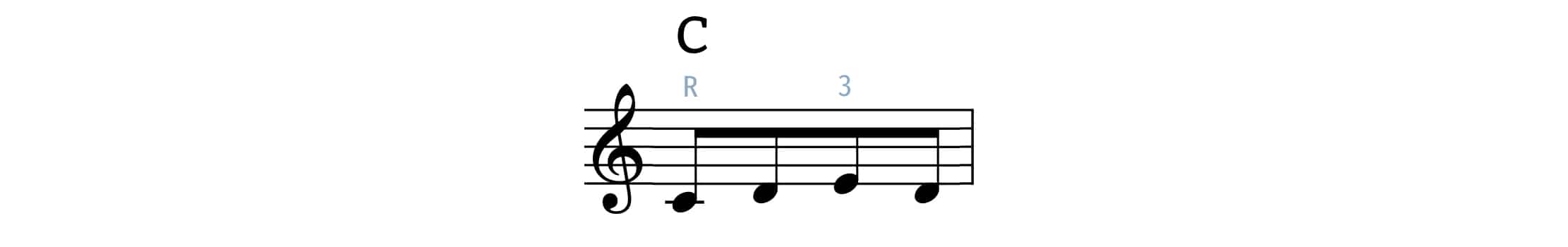

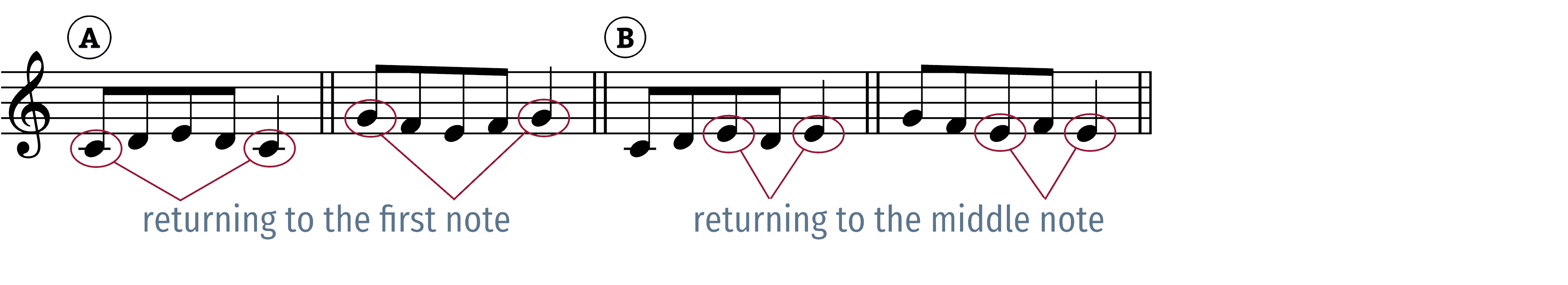

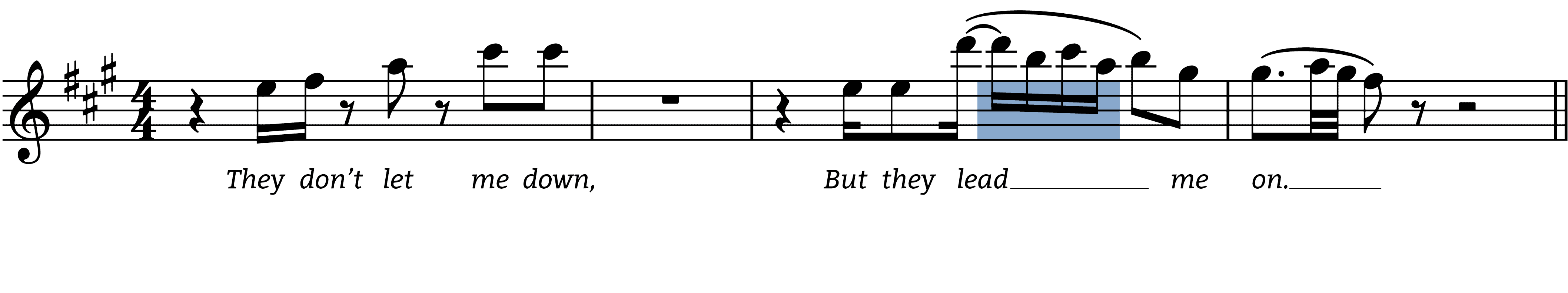

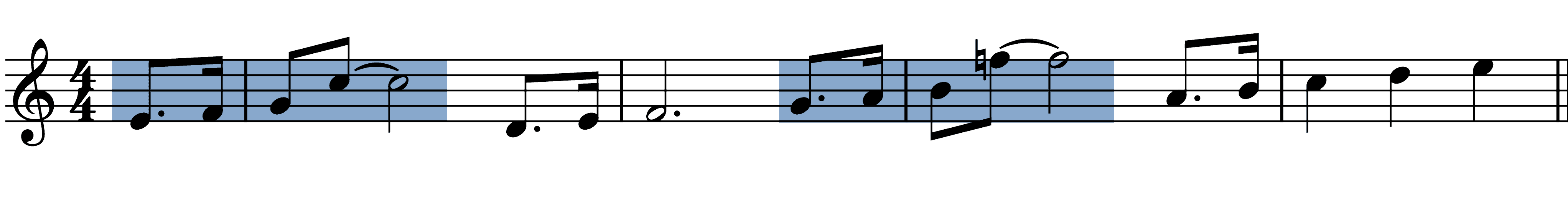

3. Exposure through reading.

Musicians who read scores see melodic figures visually, especially when melodies flow in a constant rhythm (as in the Hanon exercises) because the beams “bracket” the notes of each figure into a neat little packet. For those who don’t read traditional notation, MIDI notes in a DAW appear on a grid, revealing visual patterns as well.

“Exercise #1,” from The Virtuoso Pianist

WRAPPING UP: WHY DON’T WE HEAR ABOUT MELODIC FIGURES ANYMORE?

Oh my. It seems that the three points above point to another reason why we don’t we hear about melodic figures anymore: O V E R E X P O S U R E.

Like a fish living its entire life in water, our musical environment is so saturated with melodic figures that we don’t even notice them. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t. Just imagine what might happen if you did?

- Compose by Choice, Not Chance. Let you natural instincts spark ideas, then apply skill and acumen to refine and shape them into something more robust.

- Break the Mold. Tired of having all your melodies sound alike? Expanding your pallet with melodic figures—especially the ones you tend to ignore—will help you break out of a rut.

- Discover Your Hero’s Secrets. Once you know the building blocks of melody, you can listen to any melody with sharper precision and deeper insight.

- Fuel Creativity. Creative breakthroughs often start with setting limits. Restrict yourself to one or two melodic figures, and let the challenge force you to take unexpected paths.

Hope you’ve enjoyed this post. Please don’t forget to add your comments or questions.

Through your book and your blog posts (especially the one about the Beatles), I was able to understand melodies the first time in my life. Since I found all this stuff two years ago, things were never be the same again. So, thank you, thank you, thank you for your work.