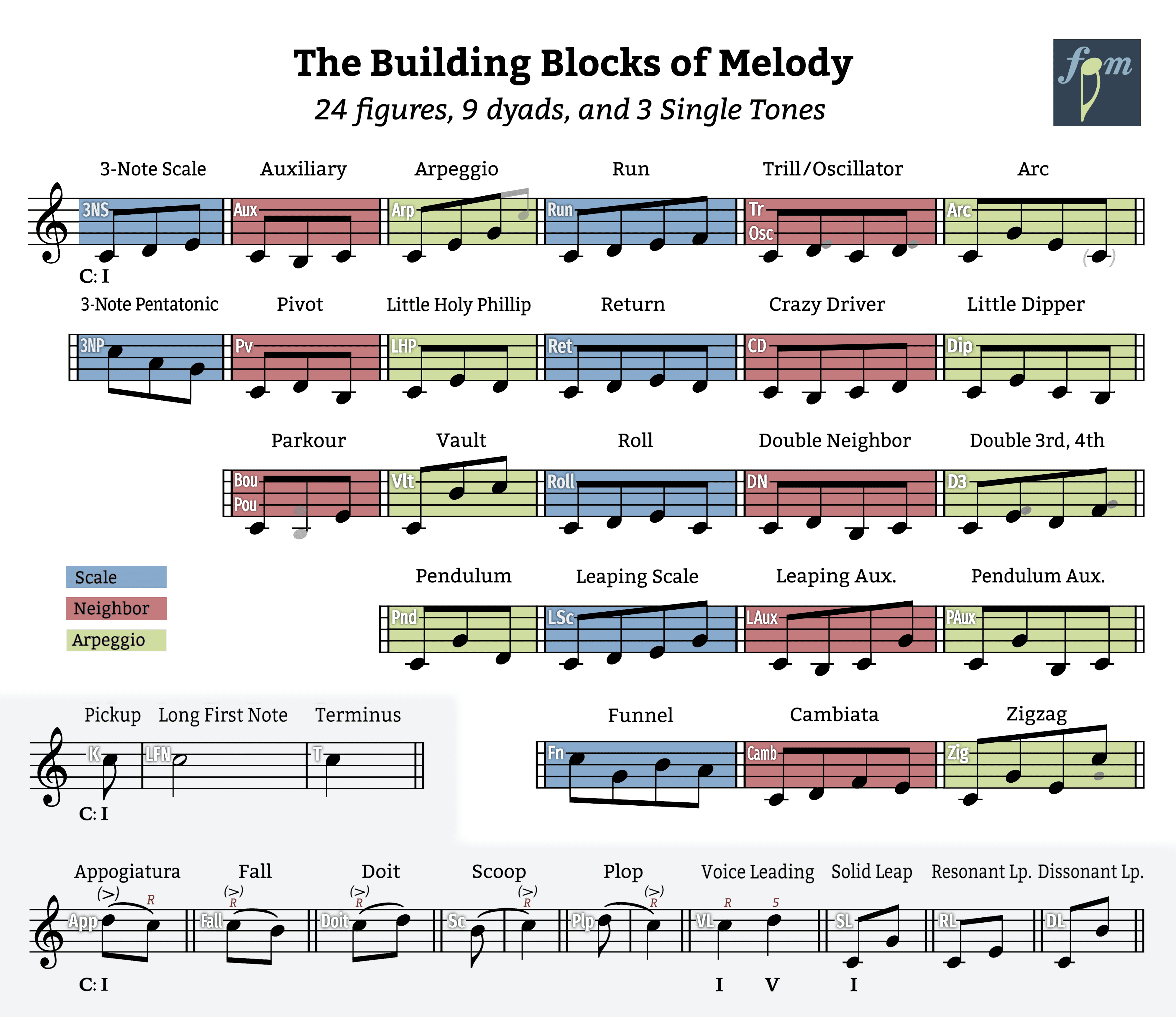

Every melody you know, plus those you don’t yet know—heck, even the ones YOU WRITE YOURSELF—are made entirely from just 32 melodic building blocks:

- 24 melodic figures (each 3 to 4 notes long)

- 9 melodic dyads (two-note combinations), and

- 3 types of single tones.

We absorb the basic patterns of melody just like language—through exposure over time. Without even realizing it, we internalize these patterns until they become second nature. For musicians, melodic figures take root in our ears, vocal cords, and fingers.

Though we’ve been using them for years, no one has ever tried to capture the intuitive language of melodic figures in writing—until now. That’s why our interaction with the building blocks of melody continues to operate just below the surface.

But it doesn’t need to. Not anymore.

The table below reveals each figure in its simplest form. And the table is INTERACTIVE! Click on any figure to open a window to hear each building block as it appears in excerpts from well-known songs across a range of styles.

the 3-Note Scale

At the heart of the 3-Note Scale lies the most resonant sound in music: the harmonic third. Thirds form the harmonic foundation of music throughout the world. We rely on them to construct chords, contrast emotions, and harmonize songs around a campfire with our friends. What does this have to do with the 3-Note Scale? The 3-Note Scale takes this most crucial element of harmony and turns it into a little melody.

“But,” you protest, “it’s so boring. Step-step up; or step-step down. How can I write an interesting melody from such a nothing?”

That’s like asking how so much astounding architecture can arise from combining rectangles, or how so many life forms from the carbon atom. Wherever we look in our universe, we find that the most crucial building blocks are also the most humble.

The excerpts I’ve chosen barely scratch the surface of what the 3-Note Scale can do—the incredible variety of emotions and ideas it can produce. You’ll hear a folk song that captures our common desire for meaning followed by its polar opposite: a cocky, flirtatious strut. Finally, the piano concerto theme feels immensely personal, like something between a dream and a diary entry.

“Blowin’ In the Wind,” by Bob Dylan

“Cool,” by the Jonas Brothers

“Piano Concerto #3,” by Sergei Rachmaninoff

the Auxiliary

In general use, the term “auxiliary” refers to something that adds to or extends the capabilities of something else. So when you add a printer to a computer, the printer becomes an auxiliary device.

And so it is with the melodic figure dubbed the Auxiliary. We hear its main note, a chord tone, two times: once at the beginning, then again at the end. The add-on note – the auxiliary portion of the figure – is an upper or lower neighbor note.

“Silent Night,” by Franz Xavier Gruber

As far as “extending the capabilities” of the chord tone we turn into an auxiliary, take a moment to try to imagine the melodies below with repeated notes rather than the auxiliary tones the composers heard fit to include.

“Bad Romance,” by Lady Gaga

“Toreador Song,” by Georges Bizet

the Arpeggio

To create an arpeggio, we perform the notes of a chord one at a time rather than simultaneously.

Groups of notes written first as a chord, then an arpeggio

Now there’s no rule that says we must begin at the bottom and run through the notes in order or the top and cascade down. In fact, there are many different patterns you can make with nothing but chord tones. And that’s why we have so many types of arpeggio figures.

But when we do perform the notes of a chord in order without changing direction, we get the simplest of all the arpeggios, the Arpeggio.

“Ring of Fire,” by Johnny Cash

“Sesame Street,” by Franz Xavier Gruber

“On the Beautiful Blue Danube,” by Johann Strauss Jr.

the Run

The word “run” is already in use in music. It either refers to a long scale or a somewhat fancier bit of melodic fluster (sometimes called a “riff.”) At FiguringOutMelody.com, the melodic figure we call the Run is exactly four notes long, and those notes always form a scale.

Of the many ways to use a Run, one easily comes out ahead of the rest. The Run often paints in broad or medium-long strokes. Sometimes these gestures join together to cover a large amount of registral space (as in “Penny Lane”). Other times, they don’t move very far but sway over a secure foundation (as in “As Time Goes By”) But Runs can also have a far nimbler side as we hear in “Wachet Auf.”

“As Time Goes By,” by H. Hupfeld

“Overkill,” by Colin Hay

“Wachet Auf, Ruft Uns Die Stimme,” by J.S. Bach

the Trill/Oscillator

Here’s a case where we have two very similar figures that count as one. (The other instance is the Parkour figures.)

The Trill. Outside of FOM, a trill is a melodic embellishment produced by rapidly alternating two notes a step or semitone apart. And the term trill also applies to the way that speakers of certain languages roll their R’s (always with great gusto). We include it as a melodic figure because so many melodies use a slowed-down version of the alternating stepwise action.

The Oscillator. When we say that something oscillates, we mean that it swings back and forth in a steady motion. If you hope to cool an entire room with a small fan, get one that oscillates. The difference between a Trill and an Oscillator is that every other note in a Trill is a neighbor note, while every other note in an Oscillator is another chord tone.

The three samples here show two possible effects of the Trill. “A Modern Major General” uses the alternating notes to create interest during what is essentially a rap. The Trill figure in “Iron Man” resembles a true embellishment, though of course, slower. The third excerpt is an example of an Oscillator.

“A Modern Major General,” by Gilbert & Sullivan, with new lyrics by Randy Rainbow

“Iron Man,” by Black Sabbath

“Over the Rainbow,” by Harold Arlen

the Arc

There are a lot of different types of arpeggio figures. If you hope to keep them straight, watch for two things. First, each type of arpeggio figure has a unique shape. (The one we’re looking at now, is shaped like an arch.) Second, that shape results from calculating the direction of each leap. To produce an Arch, we leap twice in one direction and once in the opposite direction. Or once in one direction, then change direction for the last two leaps.

The size of the leaps doesn’t matter, though when all the leaps are roughly the same size (as in the first two figures), we get a more balanced arch.

By far, most arch figures equally-proportioned leaps, as reflected in the excerpts below.

“I’ll Fly Away,” by Albert E. Brumley

“Royals,” by Lourde

“Surprise Symphony,” by Franz Joseph Haydn

the 3NP

3PN stands for a “3-Note Pentatonic” scale. Or more accurately, a 3-note slice of a pentatonic scale, because as you probably know, pentatonic scales (in either their major or minor versions) contain five notes, not three.

Notice that the pentatonic scale is a little wonky, what with its odd gaps every few notes. (Most “scales” move by step.)

We can divide a pentatonic scale into five different 3-note groups. When we do, four of those groups include one of the gaps illustrated above.

Note the similarities between the 3NP and its more symmetrical cousin, the 3NS (3-Note Scale). Whereas the 3-Note Scale always spans a third from first to last note, the 3NP always spans a 4th.

“Youngblood,” by 5 Seconds of Summer

“La Donna È Mobile,” from Rigoletto by Giuseppe Verdi

“Girl from Ipanema,” by Antonio Carlos Jobim

the Pivot

To pivot means to swivel or turn; to change direction. Picture a footballer using fancy footwork to drive the ball toward the goal. Don’t just “picture it.” Try to feel its kinetic momentum: moving one direction, then darting off in the opposite direction.

"Up Where We Belong" uses Pivot figures to get us to feel we are at the upper limits of what is possible.

“Up Where We Belong,” by Will Jennings, Buffy Sainte-Marie, and Jack Nitzsche

Don't miss the irony as Billy Joel sets the word "honesty" to an evasive melodic gesture.

“Honesty,” by Billy Joel

It's hard to express melancholy without sounding sentimental. Yet Rachmaninov pulls it off here by starting each Pivot figure as a strong dissonance.

“Adagio,” from Symphony #2 in E minor, by Sergei Rachmaninov

Little Holy Phillip

Nature abhors a vacuum. So does melody.

Any figure that ends opens up a gap (especially a leap of a third) invites the next note to fill up the little hole. So in the example below, versions A and B show the most predictable outcome for a melodic figure ending with a small leap. Versions C and D show how this same 3-note link can occur within one figure—namely, the “Little Holy Phillip” (L.H.P.)

So, about the name. A main principle in melodic figuration is that we make melody by connecting figures together. The end of one figure with the beginning of the next.

Now imagine that we could take a stop-frame video of the melodic motion between figures. Wouldn’t that help explain why some melodies feel continuous and others don’t?

THWANK! Stop imagining. We CAN INDEED observe the ways that figures link up, and no special equipment is required. Just track the steps and leaps to discover us all we need to know.

“Imagine,” by John Lennon

“Harry Potter Theme,” by John Williams

“Symphony No.8” II, by Ludwig van Beethoven

the Return

The Return figure gets its name from its proclivity to return to its starting note, as shown in the example below.

Outcome A below shows the most predictable destination of the Return figure: note #1 = note #5 (with note 5 being the first note of the next figure).

Outcome B shows another (less-) predictable path: note #5 = note #3. In other words, using this second option, the figure “returns” to the “middle” note, counting note #3 as “home.”

In the first two melodies below, the Return takes the most predictable outcomeas described above (outcome A). But in the third exceprt, the Strauss melody, we the Return doesn’t return. It LEAPS! The Return is one of many figures that is sometimes used for its smooth-as-silk behavior, and other times—when its natural connection is broken—to add a bit of complexity.

“Senorita,” by Shawn Mendez

“Bohemian Rhapsody,” by Freddie Mercury

“Voices of Spring,” by Johann Strauss, Jr.

the Crazy Driver

While the names of most melodic figures serve as mnemonic devices, “Crazy Driver” one is a contender for the most quirky. How can a melodic figure act like a Crazy Driver? Here's an illustration.

The designation “crazy” has absolutely nothing to do with how this figure sounds. There’s hardly a better choice for making smooth, gentle waves, as in the first two examples below. The third example shows quite a different sound, using the Crazy Driver as an ornate pickup to kick off a bit of syncopation.

“Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho,” a Negro Spiritual

“Every Breath You Take,” by Sting

“Minuet” from the String Quintet in E Major by Luigi Boccherini

the Little Dipper

The bulk of this figure is an arpeggio. The “plus” note is a passing tone or neighbor note, most often added at the end to make a smooth bridge to the upcoming note or figure (though occasionally, the non-chord tone can come at the front).

“Come Sail Away,” by Styx (Dennis DeYoung)

“Ring, Ring the Banjo,” by Stephen Foster

“Morning” from Peer Gynt, by Edvard Grieg

the Parkour

The term “Parkour” comes from the French word “parcours,” meaning “the way through,” or “the path.” If you take this to imply “moving along a logical path to find the quickest way from point A to point B,” you’re missing a key element of Parkour the sport. The Parkour practitioner intentionally looks for obstacles to jump, bounce, or scoot over, around, or under. And those who use the barriers to execute the flashiest and most difficult stunts earn greatest respect among their peers.

Melody doesn’t always take the most logical route from point A to point B, either. We can sense a strong gymnastic spirit in the two versions of the Parkour figures illustrated below. In each case, the first and third notes are always chord tones, and there’s a clear and direct route between them. That direct route is indicated by a shadowed notehead.

As you study the Bounce and the Pounce, don’t just try to memorize the formulas. No, no, no! Instead, picture yourself crouching and leaping, or leaping then shuffling your feet to regain your balance.

“My Favorite Things,” by Rogers & Hammerstein

“I Love You,” by Billie Eilish

“Triumphal March,” from Aida, by Giuseppe Verdi

the Vault

The Vault has two things in common with the two Parkour figures (the Bounce and the Pounce) 1. It’s a 3-note figure that takes an indirect route between the two outer notes, typically chord tones.* and 2. It contains a step and a leap, though not always in that order.

The main difference from the Parkour figures (the Bounce and the Pounce) is that the Vault’s step lies inside the outer notes of the figure.

“Hush, Little Baby,” by Carolina folk song

“The Swan,” by Camille Saint-Saens

“Maria,” from West Side Story by Leonard Bernstein

*At least the outside notes are usually two chord tones. Remember, with figuration, we focus on shape, which means that sometimes, chord tones and non-chord tones can get redistributed.

the Roll

The Roll has two component parts: a 3-Note Scale plus a leap of a 3rd in the opposite direction to the 3-Note Scale. The result is a figure where the first and last note of the Run always match, whether the 3-Note Scale comes at the beginning or end of the figure.

“Hava Nagila,” an Hassidic folk tune

“Stand By Me,” by Ben E. King, Jerry Lieber, and Mike Stoller

“The Cancan,” from Orpheus in the Underworld, by Jacques Offenbach

the Double Neighbor

The Double Neighbor figure gets its name from tabulating the number of non-chord tones present. We hear one “main note”—a chord tone—twice: at the beginning and the end.

The two notes in the middle are both neighbor notes—one higher than the chord tone; one lower. This creates a little “illegal” hole in the middle. Why is it illegal? Because one of the primary rules in melody forbids leaping between non-chord tones. But here is an immensely popular figure that does just that! Perhaps this is why the Double Neighbor figure is one of the only patterns that is already universally recognized as a melodic figure? Theorists figured they’d better proactively name one of the only acceptable exceptions to one of their staunchest rules.

“Mona Lisa,” by Nat King Cole

“If I Can’t Have You,” by Shawn Mendes

“Waltz” from the Swan Lake Ballet by Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky

the Double Third

The Double 3rd figure gets its name from the way it melodicizes a common method for harmonizing a simple scale in thirds. But rather than playing the thirds simultaneously, they are stretched out in time.

“Invention #1,” by Johann Sebastian Bach

“Cherish,” by Terry Kirkman

“Sidewalks,” by The Weekend

the Pendulum

The pendulum has two notes that move (or “swing”) by step as if swinging from a middle “fixed” note.

“Norwegian Wood,” by Lennon & McCartney

“Eastside,” by Benny Blanco, Halsey, and Khalid Robinson

“Juliet’s Waltz,” by Charles Gounod

the Leaping Scale

The Leaping Scale is a 4-note figure made from two elements: a 3-Note Scale plus a leap to a different chord tone. (if the isolated chord tone matched the first note of the figure it would be a Roll.) Either the scale or the leap can come first. The leap can be small or large. And the direction of the leap can match the direction of the scale or contradict it.

Two factors make the Leaping Scale harmonically vivid. First, the outer notes of the 3-Note Scale are chord tones. And second, the leap occurs between two chord tones. Typically, this means that each Leaping Scale contains a root, third, and fifth.

“Old Town Road,” by Lil’ Naz

“Prelude,” from Suite #2, for unaccompanied ‘cello by J.S. Bach, bars 26-31

“The Raiders March,” by John Williams

the Leaping Auxiliary

The color-coding on the table of 24 common melodic figures shows three main categories of figures: scale, neighbor, and arpeggio. But as you look and listen closely to each of the 24 figures, you’ll hear some scale figures that include one or more leaps; You’ll notice that at least one neighbor figure contains a 3-note scale; And you’ll discover a fair bit of neighbor motion in figures that are mostly arpeggios.

In short, many of the melodic figures on the table are hybrids. But because hybridism is so rampant, there’s not much point in treating it as anything special.

So how do we decide whether to put a melodic figure in one category or another? There are two things to look for. (1) Majority rules. Is most of the figure a scale, neighbor, or arpeggio? and (2) Behavior. Does the figure act as a scale, neighbor, or arpeggio?

The Leaping Auxiliary (L.Aux.) is 3/4 neighbor figure, plus a chordal leap. The auxiliary or the leap may come first or last. The leap can be in any direction relative to the auxiliary. Here are but a few possible combinations.

“Breakdown,” by Tom Petty

“Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay,” by Otis Redding

“Pavane,” by Gabriel Fauré

the Pendulum Auxiliary

The Pendulum Auxiliary is an amalgamation of two 3-note figures: the Auxiliary and the Pendulum.

“What’s Goin’ On,” by Marvin Gaye, Al Cleveland, and Renaldo Benson

“Hold Me Now,” by Tom Bailey, Alannah Curie, and Joe Leeway

“The Hallelujah Chorus,” by George Frideric Handel

the Funnel

The Funnel offers some of the most convincing evidence that composers imagine shapes as we compose. How else can we explain the ever-narrowing series of leaps that make up this figure? Perhaps as a backward extension of the Little Holy Philip? Keep that in mind as you listen to “Someday My Prince Will Come,” where the pattern stretches back even further.

We classify the Funnel as an arpeggio because it leaps until it runs out of room, not because it spells any particular harmony. In fact, the Funnel has the most ambiguous harmonic structure of all the figures, which is to say that it doesn’t fit into any particular harmony. Even if we find a way to separate chord tones from non-chord tones in one instance of the Funnel (and good luck with that!), it's not likely to work out the same way in other appearances.

“Someday My Prince Will Come,” by Larry Morey & Frank Churchill

“Dreams,” by Stevie Nicks

“Great is Thy Faithfulness,” by William Runan and Thomas Chisholm

the Cambiata

Most of the names for the 24 Universal Melodic Figures have a mnemonic function. The name tells you something about the figure that not only helps you remember it but use it. Not so with the Cambiata figure. The figure traces back to 17th-century Italy and derives its name from an Italian verb meaning “to change.” If it were clear to anyone what sort of change occurs within this figure, that might end up being helpful. But no such luck. I only use the name Cambiata because that’s what other people call it, which brings up an interesting point about figure names.

The Cambiata is one of two figures that use standardized names. The other figure is the Double Neighbor, which sometimes goes by the name “changing tone” (in English). Why do none of the other 22 melodic figures have names? Likely because they are so ubiquitous that nobody thinks they deserve special recognition.

The behavior that merits special recognition in the Cambiata (and also the Double Neighbor) has to do with the “hole” in the middle of each figure. Music theorists have never known how to explain how a figure that leaps to and from dissonant notes can sound so graceful. So they simply provide guidelines for how to handle it, never bothering to elaborate on the “broken rules.”

We won’t go into the strict guidelines for using the Cambiata in classical styles here. More important is that the attractiveness of this figure comes from the way it goes “too far” (passing its destination) before returning to the intended goal. It’s a routine we’ve encountered in the L.H.P. and the Double Neighbor.

“There Goes My Life,” by Kenny Chesney there-goes-my-life

“Cheek to Cheek,” by Irving Berlin

“The Washington Post March,” by John Phillip Sousa

the Zigzag

The Zigzag figure changes direction after every note, making it the most indirect way to arrange the notes of a single harmony. Now typically in figuration, the more times a melodic figure changes direction within itself, the more complicated it sounds and feels. This is certainly true of the other two figures that change direction after every note: the Double Neighbor and the Double Third. But for some reason, the Zigzag figure usually makes a melody sound more playful than elaborate.

“Your Smiling Face,” by James Taylor

“Trumpet Concerto in Eb Major,” III by Franz Joseph Haydn

“Die, Die, Die,” by the Avett Brothers

Single Notes

In melodic figuration, we find only three ways to use single tones: [1] as a Pickup (P), [2] as a Long First Note (LFN), and [3] as a final tone, which we call a Terminus (T).

THE PICKUP

A pickup is a metrically weak note or notes that lead(s) into the first true downbeat of a melodic gesture or phrase. Pickups can range in length.

Some pickups consist of but a single tone. It’s such pickups that we label “K,” especially when the pickup anticipates (pre-repeats) the upcoming note on the strong beat.

“The Stars and Stripes Forever,” by by John Philip Sousa

When the pickup steps or leaps to its upcoming destination, we have a choice to either label it as a simple pickup (“K”) or as a melodic dyad, in ligature alignment.

“My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean,” traditional Scottish folk song

THE LONG FIRST NOTE (LFN)

A great many melodies don’t start off with a melodic figure or even a pickup. Instead, they begin by holding out or repeating a single tone that isn’t part of the melodic figure (or Terminus) that ensues thereafter. It’s this factor—not being fully integrated with the melodic figure that follows—and not length that makes an LFN and LFN.

it-is-well-single-notes

“Let’s Stay Together,” by Al Green

An LFN needn’t be held out to count as a long first note.

“Money,” by Roger Waters

A song can have a pickup to a LFN. “I Walk the Line” contains all three types of single tones: a Pickup, a Long First Note, and a Terminus (which I explain next).That leaves only one actual melodic figure (the Roll) in this phrase.

“I Walk the Line,” by Johnny Cash

THE TERMINUS

A terminus is any note that ends a melodic gesture that is not part of the figure or dyad that precedes it.

“It is Well With My Soul,” by Phillip Bliss

Stepwise Melodic Dyads

Among the nine possible melodic dyads:

(1) Five melodic dyads move by step.

(2) One type of dyad, “voice leading,” can move by step or leap.

(3) Three melodic dyads move by leap.

These distinctions will serve as an outline for our brief introduction. Why do we need more detail to recognize (2-note) melodic dyads than (3- to 4-note) melodic figures? Try for yourself. Look at the first 6 dyads on the chart above. They all move by step. What’s to distinguish one from another?

So glad you asked!

STEPWISE DYADS

We use three factors to tell one stepwise dyad from another.

Harmony. One note will be a chord tone. The other note will be a non-chord tone. The fact that either can come first is why we have several designations. The reference point for stepwise dyads is always the consonant note: whether it comes first or last; whether it is accented or unaccented.

Metric placement. One note will be “accented”—metrically stronger—than the other note. So the question becomes: Does the first note of the dyad move “into” the second note? Or does the second note “spring out from” the first?

Direction. One note will be higher than the other—by one step (or half step). The question is: Does the dyad step up or step down?

1. The Appoggiatura (App)

An accented dissonant note resolves downward by step, at least 93.2475% of the time.

“Yesterday,” by Paul McCartney

The very last appoggiatura in this next excerpt resolves upward.

“Allegro,” from Piano Sonata #13, K.333 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

2. The Fall

Normally, descending stepwise motion that starts on a strong beat creates an appoggiatura. But not when the first note is a chord tone. The Fall starts with an accented chord tone descends by step to an unaccented non-chord tone or b7th.

“Mellow Yellow,” by Donovan Leitch

3. The Doit

(pronounced “doyt”): a stepwise lift AWAY FROM (after) an accented chord tone.

“September,” by Earth, Wind, and Fire

4. The Plop

A unaccented stepwise fall TO (before) an accented chord tone, making the Plop a type of pickup.

“All I Have to Do is Dream,” by Boudleax Bryant

5. The Scoop (Sc)

An unaccented stepwise pickup from below, making the Scoop a type of pickup.

“Get Back,” by Lennon & McCartney

VOICE LEADING

The term “voice leading” refers to how each “voice” or “part” in one chord moves smoothly (which is usually the goal) to its corresponding “voice” or “part” in the upcoming chord. Anyone who has studied traditional “part writing” in a music class will be familiar with S-A-T-B (soprano-alto-tenor-bass) exercises.

Here are three chords voiced smoothly in S-A-T-B part writing.

What does this have to do with melody? Some melodic dyads result when the top voice of one chord moves to the top voice from a different chord. That means that both notes of the melodic dyad are consonant. This, above metric placement (whether or not both notes of the melodic dyad are accented, unaccented, or one of each) is the factor that qualifies a dyad as “voice leading.”

“Bye, Bye Love,” by Boudleaux and Felice Bryant

“Waltz of the Flowers” from The Nutcracker, by Pyotr Tchaikovsky

Leaping Melodic Dyads

We need but one factor to tell leaping dyads apart: the harmonic nature of the leap.

Traditional melodic practice has two buckets for separating harmonic leaps: consonant and dissonant. As far as dissonant leaps, melodic figuration treats them the same way as traditional practice. Leaps of a 7th or 9th, as well as all augmented or diminished leaps all end up in the dissonant bucket.

However, we split the consonant bucket into two compartments: (1) solid leaps (of a perfect interval) and (2) resonant leaps (of a major or minor interval). The designations “solid” and “resonant” describe the effects of such leaps. Once you hear the difference, you can’t unhear it.

1. The Solid Leap (SL)

Perfect intervals—unison, fourth, fifth, and octave—have a grounded, open, and secure quality that contrasts with the sonorous, shimmering resonance of thirds and sixths. The term "perfect" reflects a blend of mathematical, philosophical, and theological ideas that evolved over centuries, but another fitting term for these intervals might be "solid." Their harmonic simplicity and lack of tension make them feel sturdy and stable, as if anchoring the music. This solidity is evident in genres like power rock, where chords often omit thirds, leaving only the root and fifth to create a raw, robust sound.

Another common place to hear solid intervals is in music that uses “horn calls,” though power rock and fanfares are hardly the only occasion for including something solid in a melody.

“London Symphony #104 in D,” I, by Frans Joseph Haydn

2. The Resonant Leap (RL)

As mentioned previously, 3rds and 6ths have a more sonorous, gentle quality than 5ths or 8ves.

“Colonel Bogey March,” by Lieutenant F. J. Ricketts

"The Gambler" uses solid and resonant leaps to offer advice about playing poker. The first phrase urges, “If you get got good cards, stand your ground.” And the last two words of that phrase, "hold 'em," are sung over a solid leap. The second phrase admits, “You gotta know when to quit.” So the words "fold 'em" are sung over a resonant leap, emphasizing the don’t-sweat-it attitude toward letting go.

“The Gambler,” by Kenny Rogers

3. Dissonant Leap (DL)

It’s amazing that songwriters find so many great ways to use supposedly “dissonant” leaps that are far more expressive than harsh.

“Somewhere,” by Leonard Bernstein

“Got to Get You Into My Life,” by Lennon & McCartney

SOME FINE PRINT

2-note pickup, or 3-note ligature?

Some dyads are not really dyads. It’s best to think of 2-note pickups as part of a 3-note ligature figure. (Remember that ligature alignment puts the last note of a figure on the upcoming beat. We label it by putting a forward slash / after the figure label.) In other words, the 2-note pickup grabs the first note of the upcoming figure to make a 3-note figure that places its last note on a beat. Compare the two options in “What a Wonderful World.”

“What a Wonderful World,” by George David Weiss and Bob Thiele

Perforated melody

You’ll notice that I’ve also marked version B above not as melodic dyads, but as melodic figures that get separated by rests. (Put them back together again and you’ll hear “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star”.) This is an effective technique to remember; one of many that are possible by playing with single notes and melodic dyads.

For more about why you’ve never heard of melodic figures before, click here.

Here are FIVE reasons why understanding melodic building blocks can transform the way you write, hear, and think about melody.

1. Composers of every era have relied on the same core building blocks. Melodic figures are timeless. From Bach and Mozart to The Beatles, Adelle, Quincy Jones and beyond, composers across centuries have drawn from the same basic patterns. Learning them isn’t abstract theory—it’s the very foundation behind building melodies that stand the test of time. Understand melodic figures, and you connect to a tradition shared by the greatest composers, while also gaining tools to shape music that feels fresh and personal.

That means that we can…

2. Think of melodic building blocks as the Legos of melody—ready-to-use pieces that we instinctively weave together, pull apart, and reassemble to better express what we know we need to say. You’ve been using them your entire musical life without realizing it. But learning to recognize and shape these blocks gives you access to the underlying structure of melody, making your compositions more cohesive, striking, and easier to develop.

3. Use melodic building blocks to transform rough ideas into polished melodies. As a composer, you already work with melodic building blocks intuitively. Why not take control of them? Instead of relying solely on trial and error, use your instincts to map out a general idea (a rhythm or phrase shape), then use melodic building blocks to refine that raw draft into something more polished and expressive.

4. Melodic figures give you more creative control over your musical voice. Writing melodies doesn’t have to feel like wandering in the dark. A working knowledge of melodic building blocks can provide countless options, giving you more control over where your melody can go next—even setting up melodic plot twists!

5. Melodic building blocks make composing feel less like starting from scratch. Even the most original melodies are rarely crafted note by note. Beneath the surface lie familiar patterns—melodic building blocks—that composers instinctively arrange and reshape. Recognizing these patterns makes melody writing feel less like inventing from nothing and more like refining something that’s already there.

Be sure to look around the rest of the FOM site to learn more about how to use melodic figures in your own music. And please tell me what you think about melodic building blocks in the comments.